Still let my tyrants know, I am not doomed to wear

Emily Bronte

Year after year in gloom, and desolate despair;

A messenger of Hope comes every night to me,

And offers for short life, eternal liberty.

If dogs run free, then what must be

— Bob Dylan, “If Dogs Run Free”

Must be, and that is all

True love can make a blade of grass

Stand up straight and tall

In harmony with the cosmic sea

True love needs no company

It can cure the soul; it can make it whole

If dogs run free

He was swept with a sadness, a sadness deep and penetrating, leaving him desolate like someone washed up on a beach, a lone survivor in a world full of strangers. – Robert Cormier

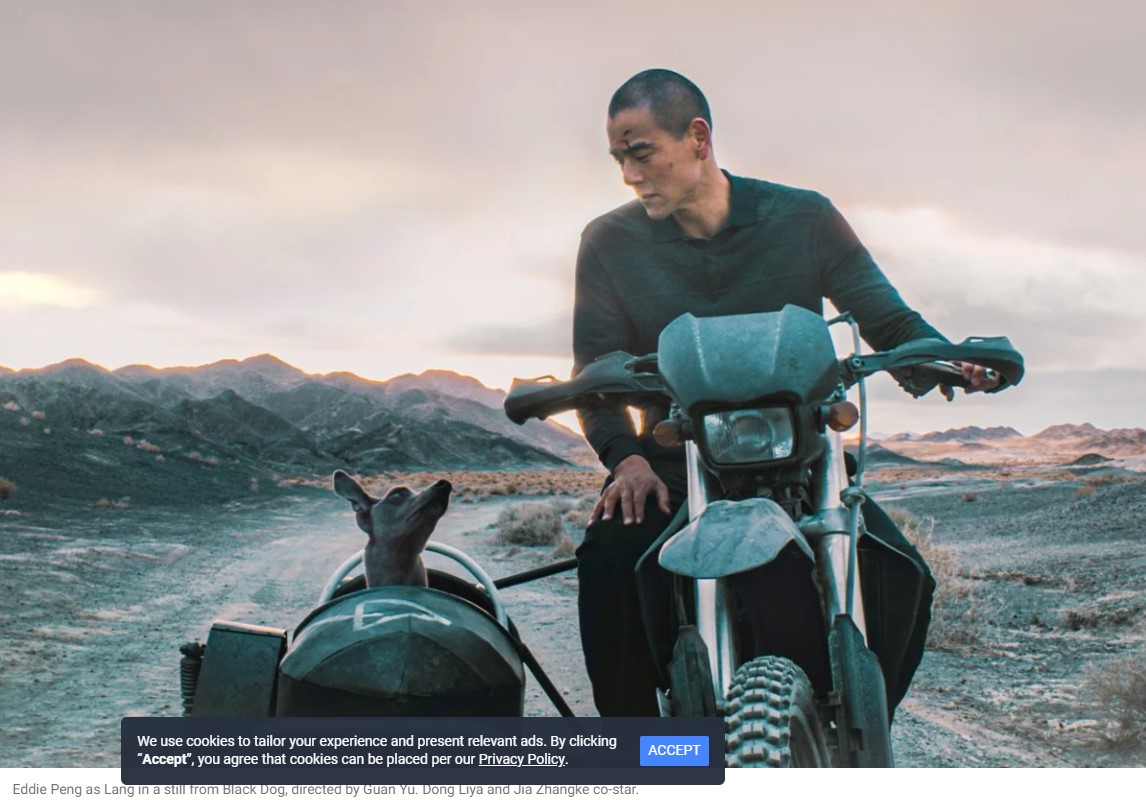

Black Dog, Chinese film director Guan Hu’s 13th feature film, bagged the Un Certain Regard Award at the recently concluded 2024 Cannes Film Festival.

The film, which, according to this critic, expectedly and rightfully picked the prestigious award, is more than the sum of its simplistic titular title.

That the film, pipped 17 other features in the Cannes Film Festival’s second-most prestigious competitive section, to win the first place, eight of which were debuts, also competing for the Caméra d’or, speaks of the director, who has a string of films to his credit beginning with 1994 Dirt, considered an important example of the Sixth Generation movement that emerged in China after the Tiananmen Square protests of 1989. The film spotlighting on the nascent rock music scene of Beijing.

That, Guan Hu, whose works transcend several genres and thematic concerns, and hailed as an important voice of the sixth generation of Chinese film makers, in his very debut at Cannes, should hit the bull’s eye is quite noteworthy.

This, in itself, speaks of the film’s larger import than the simplistic title actually suggests as also the director’s change of trajectory in his cinematic oeuvre. And as the Jury President Xavier Dolan unequivocally lauded the film for “its breathtaking poetry, its imagination, its precision … its masterful direction.”

Yes, the film does revolve around its principal feral protagonist Black Dog aka Mashing. In fact, over 100s of its canine community of strays, are on the run, fleeing from the clutches of the dog catchers out to remove them to the pound and put to death, thereafter, on executive orders.

But, Black Dog, the film, also stands as a highly political film as well, as a metaphorical and allegorical testimony to the unilateral doings of the People’s Republic of China, prior to, and in preparation for, the 2008 Olympic Games.

The move leading to mass displacement of people from their homes in the villages to State built structures so that the country could host and basic in the glory of the Olympic Games.

As the film plays out tracking the man-animal duo of Lang & Mashing, it also becomes increasingly obvious that Guan Hu is also subtly snaring audiences to the doings of the powers that while taking on vast construction projects required to host an Olympics rarely spares a thought to fiscal activity that benefits common citizens.

It is obvious that with projecting the country on the global stage as a prosperous one to showcasing its rapid advancements in hosting events, despotism and political corruption takes the better of things in driving common people seen as impediments to progress, authoritatively shunted away to the fringes to makeshift encampments so that big ticket projects find a smooth fruition in meeting deadlines.

It is this underlying troublesome thematic concern that Black Dog seeks to directly engage its audiences and the price actual citizens pay when a country seeks to hot such mega events running roughshod of their lives and living.

That setting becomes the strongest aspect of “Black Dog,” which takes place in place in the shadows of the Olympics as the people being displaced by the pageantry lead lives of quiet desperation.

Adopting the neo noir genre of cinematic style, the film, follows a former convict, who, in the course of tasked duty of clearing the strays in his remote hometown on the edge of the Gobi desert forms an unlikely connection with the said pet pal Mashing.

As the film’s director, speaking at the film festival, states on the inspiration behind the film, that “living in China, I have experienced China’s tremendous development over the past decades first hand. I have always been curious to know what life has been like for people in places outside the big cities and in more remote parts of China during this rapid period of development. My interest in, and reflections on these groups of people, are what inspired me on this film.”

True. Even as Hu focuses and tracks the symbiotic relationship between a laconic Lang and Mashing, as they bond and bike around the vast expanses of the Gobi desert, he also subtly and in a nuanced manner also brings to fore the trials and travails of the people of the nondescript coal mining town forced to leave their homes and be housed elsewhere far from the limelight that Olympic Games would put their country on.

Fresh from his highly successful twin films of 2020 – the war epic The Eight Hundred and the Korean war drama The Sacrifice – Guan Hu takes a directorial change in Black Dog, set in the sprawling Gobi Desert and the vast expanses of North Western China.

Out of prison, a stoic and reticent Lang, returns to his hometown, on the outskirts of the Gobi Desert, where, prior to his 10 years incarceration, was a local hero with a fandom following for his stunts with motorcycle in the death well of the local circus and also a czar of rock music.

With jobs hard to come by given his background, Lang latches on to the task of ferreting out strays infesting the town. One such mission results in his encountering the Black Dog Mashing, a rangy hound rumoured to have rabies.

Sumptuously shot by cinematographer Gai Weizhe who makes the most of the visual and scenic landscape opportunity that the Gobi desert canvas provides, Guan Hu ensures his expansive cinematic treatise convey more than the man-animal companionship through the sub-text of the narrative that unfolds simultaneously.

The decimation of the entire town, housing the derelict homes done in by the ravaging desert winds, by the authorities, and the mass migration of the people to housing colonies mandated for occupation, provides the underlying subtle and hidden metaphor of Black Dog.

Of course, the film also speaks about the redemption of a socially outcast man, who pushed to the fringes of society, finds companionship with the much feared and misunderstood Black Dog, a mute, as a reciprocating mate.

The canine friend’s innate feral quality for survival emboldens an otherwise desolate and rather cynical Lang to look at life differently and embrace the prospects that lie ahead of him.

Magnificently picturised, Black Dog turns into a melancholic, moody and moving fable of both Lang and Mashing as also the people that are led to suffer the displacement and disruption in the wake of development that has no place for them in the larger scheme of social schemes.

Epic and panoramic in its scale and sweep, imbued with that quintessential stylistic quality of a generic Western, Black Dog, through the reflection and repentance of the deed that sent Lang behind bars, also comes across as a caustic social commentary swamped in the fatalistic mood of the rather desolate and descript place that is existing on borrowed time, bringing to fore the struggles of people trying to overcome their otherwise foreordained fates.