Women.

Faceless.

Nameless.

Unacknowledged.

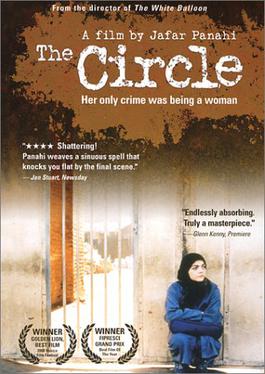

These are the women from Jafar Panahi’s ‘The Circle’. This film is originally called ‘Dayare’ – Restrictions or Aukat as they say in Hindi, a word easily used for women. And fits Panahi’s characters from the said film. This isn’t a story of one woman. In fact, he talks about the plight of several faceless and nameless women in Iran.

The film starts with the birth of a girl. The titles are juxtaposed with a woman’s screams of labor pains and by the time the credits end, we hear the cries of a newly born baby. A nurse opens a small window and calls for Solmaz Golami. Golami’s aged mother walks up to the window, when the nurse tells her, “It’s a girl. She’s cute and both the mother and the baby are doing fine.”

Even though the aged mother’s back is towards the camera the whole time, you can feel her life is about to be engulfed in chaos. She knocks on the window again, and confirms if it’s a girl. “The sonography had told us it will be a boy,” she says. “Her husband will now divorce her.”

The camera flips around, focusing on her concerned face. She climbs down the stairs of the hospital and delivers the bad news to her second daughter.

While she gets out of the hospital, the camera pans out to three young women, who have just gotten out of prison on a temporary pass and have no intentions of going back in. But we never get to know what was their crime for which they were in the prison.

One of the women – who remains nameless in the story – is looking to sell a chain to raise money for the bus ticket. She is immediately caught by the cops. The youngest of the three – Narges – is idealistic. She wants to go back to her scenic village and meet her boyfriend, where she is convinced, she will live happily ever after. Aarezoo, a slightly older woman among the three and a more realistic one, makes peace with the fact that it would be tough for both of them to escape from Tehran.

Aarezoo decides to raise enough money just for Narges to escape, and even succeeds in doing so. She is seen meeting with a man for money, and in the next shot, she has it with her. Exactly what she did or said to the man is left to the imagination of the audience by Panahi.

The focus of the story has now shifted to Narges, who is finding it extremely difficult to even book a ticket because she is not in the company of a man. Scared and shaken, Narges returns to Tehran, looking for help, searching for Pari, another friend she had made in prison.Needless to say, the director now leaves Narges behind because the story has now moved on to Pari.

Pari’s elder brothers walk into the house and start beating her up because she has “embarrassed the whole family”. She has gotten pregnant in prison and wants to get an abortion. After being kicked out of the house, Pari gets in the taxi, looking for a friend who might help her in this situation.

After being turned down for help by two of her friends, Pari is seen walking around the streets by herself. She can’t book a room in a hotel because she doesn’t have an id card and there is no man to look after her. Pari now bumps into a mother with her six-year-old daughter. Soon we as audience and Pari realizes that the mother intends to abandon the little daughter hoping her daughter will find a decent family to raise her.

We now follow the mother, who has abandoned her daughter. A man offers to give her a lift in the streets and she is arrested on the suspicion of being a sex worker. When she is taken to the police station, we meet another woman who is actually a sex worker. She is made to stand against a wall, where smokes a cigarette. At that moment, a policeman opens a small window of the prison cell and asks, “Is there a Solmaz Golami here?”

The camera moves around the prison cell, where we see most of the women, we have seen in the film so far, before it moves back at the prison guard. It is raining outside with thunderstorms, underlying the darkness in the lives of women we have encountered so far. “She is probably in another cell,” the guard says, and the film concludes.

It is a story of a day in the life of few women who perhaps travel a full circle before submitting to their fate.

The reason I thought it was important to tell the story in details is because there is no one protagonist in the whole film. We get a bit of sense into the lives of these women and understand the larger picture. We experience their tragedies, get involved in their lives for a brief period and then wonder where they would go from here. What was their past and what would be their future? But more importantly, we realize that not a single woman here has a defeatist mindset. They are all fighting back in their own way in a deeply patriarchal society.

This is Panahi’s third film after The White Balloon (1995) and The Mirror (1997). In those films, he told the stories of children in a way most Iranian filmmakers don’t. Even while keeping children as central characters, Panahi looks to examine the larger society, rather than merely focusing on the innocence of children.

However, Panahi’s films post 2000 are in a league of his own. All his films, including No Bears that was released in 2022, have a few characteristics that are common. He doesn’t use background music at all. But even with natural sound, his films are more compelling than most you will ever see. It is said that Panahi’s films are a documentation of everyday lives of everyday people. That perhaps is the reason why the camera angles aren’t important, nor is modern technology. He tells the story in a matter-of-fact manner. Even a lighter moment doesn’t seem like strategically placed.

In ‘The Circle’, every female character leaves a mark on the audience. Through every woman we meet in the film, we live their tragedies and restrictions with which they go about their lives. While telling the story of Iranian women, Panahi makes a statement that isn’t limited to Iranian women because oppression of women isn’t exclusive to Iran. It is universal. The characters he writes and explores are relatable, and as a woman, you identify with them even though Panahi doesn’t tell their stories from start to finish.

Panahi never spoon feeds his audience. But he tells exactly what he wants to convey about the authoritarian government of Iran. His films work like a rude wake up call. While talking about the film, Panahi had said, “I remember reading a news report where a woman had killed her two children and then died by suicide. But the report didn’t mention why she did what she did. Maybe the reporter didn’t think it was important.”

He went on to say, “Most societies oppress women. And it isn’t limited to any class.”

It was impossible to have ‘The Circle’ released in Iran. But it was just the beginning. Jafar Panahi didn’t stop making films, nor did he leave the country. He faced the censorship of the government and continued to make the films that said what he wanted to say.

He paid the price for that. Still is.