When the Lumière Brothers first released their compendium of short films on 28thDecember, 1895, they simply recorded the events unfolding in front of the camera lenses. Their principal objective was to use the camera for its overwhelmingly indexical feature, i.e, the recording of realty. Later, this style of filmmaking was named Actuality (actualié in French) by film scholars. Over the next few years, this style of filmmaking became prevalent in non-fiction or documentary cinema whether it was Kino Pravda in post-revolution Russia or Cinéma Vérité style ethnography by Jean Rouche. Filmmakers like Rouche and Vertov employed an observational approach to their filmmaking. In fact, Rouche often described himself as a “fly on the wall” while documenting his subjects. These filmmakers relied considerably on the indexical quality (as C.S. Peirce theorized, an Index is the direct incontrovertible evidence of the existence of what it refers to) of an image captured through the lens of a camera. An image that was extolled for its veracity by prolific classical film theorists e.g., André Bazin. However, with the proliferation of digital image and computer-generated imagery (CGI), the indexical quality that accounted for the haecceity of a photographic image is now under serious jeopardy. As Lev Manovich quite aptly observed that post digitization, a pixelated image is just another form of painting and therefore closer to an icon rather than an index. Hence, the observational approach, albeit still viable, might not be the most politically correct one, especially dealing with subjects like gender inequality and oppression of women.

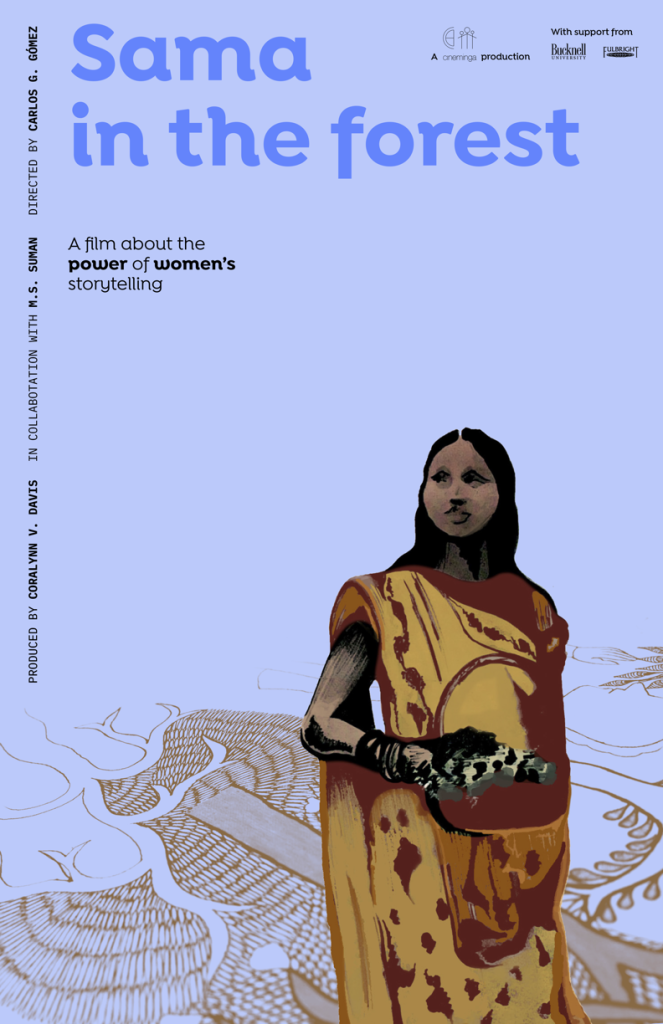

Apropos of this argument, the interactive style of the film Sama in the Forest seems to be quite appropriate in terms of its subject matter. This ethnographic documentary focuses on the Sama Chakeva festival celebrated by Maithili women as well as the rituals and works of art associated with it and endeavors to make a comparative analysis between myth and reality. As far as the myths are concerned, Sama, the daughter of Lord Krishna and Samba’s sister, fell in love with Chakeva, the son of an ascetic. However, their dalliance was cut short by a man named Chugla who desired Sama and informed Krishna about this affair. An enraged Krishna punished Sama and her lover by metamorphosing them into cuckoo birds and condemned them to live like this for eternity, despite many pleadings from Jambavati, Sama’s mother. When Samba came to know about this contretemps, he rebuked his father for his hypocrisy (as Krishna was renowned for his numerous dalliances in his youth) and ventured to meditate for a hundred years in order to bring his sister back to her human form. Meanwhile, Chugla, who coveted Sama and was dissatisfied with the outcome of Krishna’s curse, made an attempt to kill Sama and Chakeva by setting the Vrinda Forest on fire. However, his evil machinations did not come to fruition and he was burnt to death himself. Samba, with his inexorable determination to bring her sister back through meditation, finally succeeded in doing so.

In order to draw a parallel between the aforementioned myth and its relevance in a modern Maithili community, the film employs a sui generis language of commingling nonfiction with fiction. The interviews of various Maithili artists are intercut with scenes depicting the mythical narrative where the characters are portrayed by the very same artists giving interviews. The affectation engendered by this style of filmmaking is twofold. Firstly, the juxtaposition of myth and reality accentuates the striking similarity of patriarchal oppression on women depriving them of their fundamental rights to education and agency altogether. Secondly, the fact that the same people are portraying the characters and giving interviews, foregrounds the interactive and collaborative filmmaking process which is strictly antithetical to the “observational” filmmaking technique of previous documentarians. The reason behind this filmmaking choice could be the association of passive observation with voyeurism and objectification. The popular cinematic form heightens the observational property of the camera’s gaze thereby objectifying the entity in front of it. Historically, male producers and filmmakers have been objectifying women figures and characters in this manner since the advent of Classical Hollywood paradigm in American Cinema. In fact, this practice is so popular (even now) that feminist film theorists like Laura Mulvey described the gaze of the camera to be fundamentally masculine (“Male Gaze”).

Incidentally, the objectifying gaze is discussed in this film as well and there is a conscious effort in nullifying that gaze by offering unmitigated agency to the subjects (both male and female participants) of the camera. The film also diligently avoids any possible occurrence of exoticization, a fault that can be found even in the best of ethnographic documentaries made about lesser-known communities by prominent European scholars. Here too, the concept of gaze (a white imperial gaze) is carefully considered and avoided. The depiction of Maithili art and craft, juxtaposed with shots of the festival and that of the mythical story, might seem a little amateurish at times but it is successful in getting its point across as directly as possible. The correlation between Chugla (means tattling) and the deleterious effect of hearsays and gossips on a woman’s image as well as the societal violence it leads to is also quite apparent in this film.

Director Carlos G. Gomez indeed does a commendable job in constructing a diegetic world that can successfully make a comparison between the trials and tribulations of women in India belonging to two separate time periods. Anthropologist Coralynn V. Davis’ thorough and in-depth research creates a strong bastion in this aforesaid construction and so does the skillful writing of M.S. Suman. The amateurish nature of the overall film aesthetics, in a way, adds to the charm of this film as well by highlighting its collaborative and interactive characteristics. In conclusion, for a debut feature documentary film, Sama in the Forest posits considerable promise as a collaborative ethnographic film. The film shows respect to the community it is documenting while simultaneously depicting its rituals and problems without falling into the trap of a politically incorrect gaze. This documentary, de facto, exhibits that there is a viable way to depict and interpret the symbolism inherent to Indian Mythology and Religion.