The first major mass media platform that provided the public with a forum where there was socializing on a national scale was none other than the motion pictures. India is the world’s largest cinematographic industry. The two worlds of Euro-American culture and the Indian society impinge on the Indian’s psyche and for generations have influenced the filmmaking process. Indian cinema has delved into the themes of caste system, complex processes of modernization, colonialism and nationalism and representation of women. We have grown from a fascination of social themes, to rhetoric and fantasy, followed by issues of nationalism to romantic musicals. A figure of socio political nature, cinema is much more than mere settings and narration, it moves past these boundaries racing towards frames and coherence among sensual experiences amalgamating into virtual reality. Cinema has been lauded for the longest time for bringing to light realities faced in every nook of our country but we cannot ignore how commercial cinema has glorified even the goriest details. Reality ought to be considered and digested in its natural form rather than blanketed through fantasy. The new wave of cinema is popular for its strong narratives and compelling plotlines. Mainstream Indian cinema now reflects social relevance and reality. The emergence of the genre of middle-path cinema has succeeded with a growing awareness by the public of the pervasive violence and inequalities in the country

“What else is life if not loneliness and silence?”

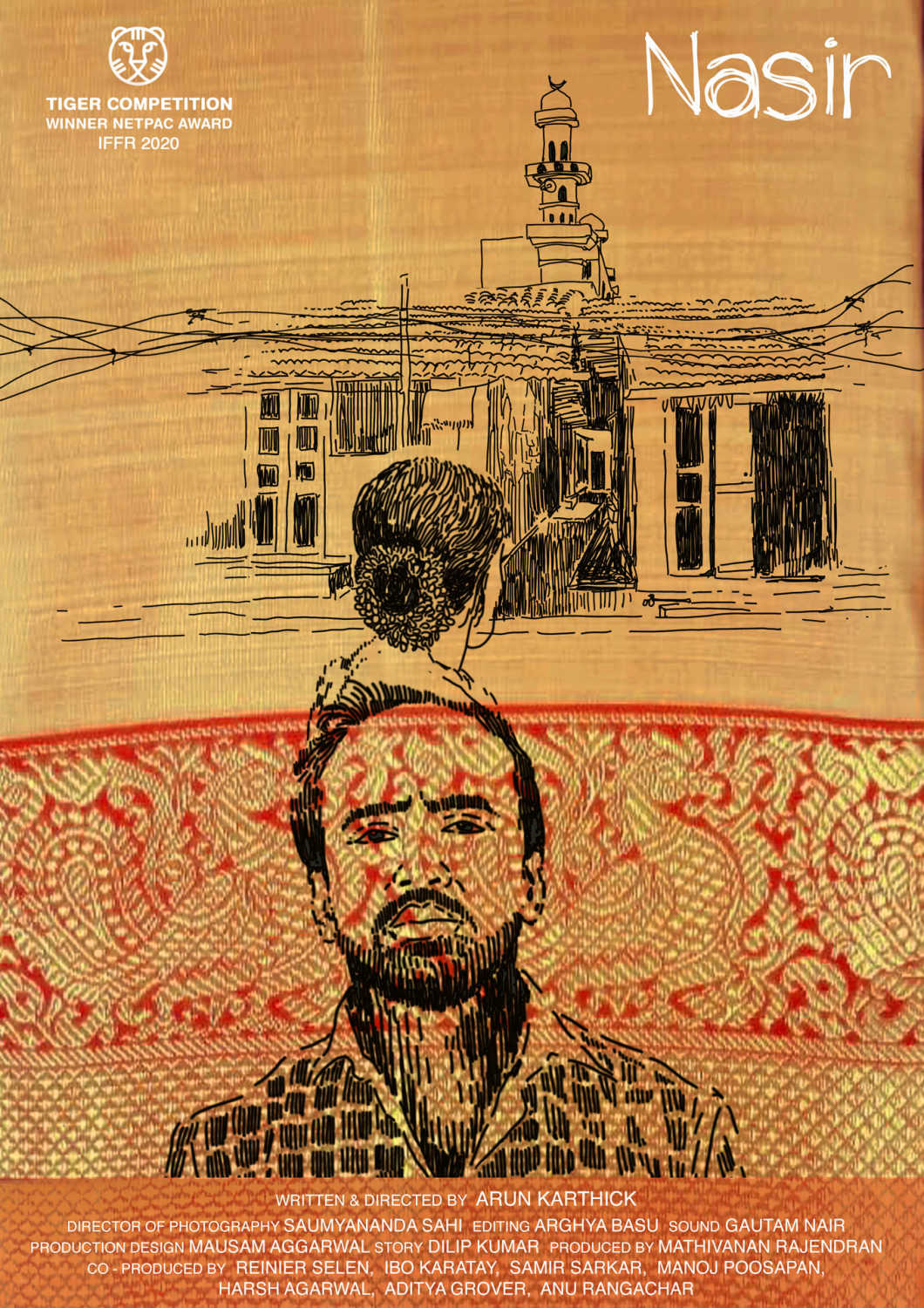

Opaque, subtle and a quiet plea that aptly conjoins the impurity of life, Humanistic values questioned with a blend of sentimentality and manipulation. Life is a thin veil of pre –conceived notions and unsettling nature. The aesthetic overlaps with the harsh realities. In the Tamil movie Nasir (2019), directed by Arun Karthick, aided by the Hubert Bals Fund from Netherlands. the titular role of Nasir is played by Koumarane Valawane. Nasir was premiered at the International Film Festival Rotterdam in 2020, as an entry for the Tiger Competition and is the recipient of the prestigious NETPAC Award for the best Asian feature film. It recently premiered on YouTube for the We Are One initiative. Although tweaked at some points, Nasir is said to be an adaptation of A Clerk’s Story, a short story by Dilip Kumar, a sensational Tamil writer depicts the tale of an eponymous protagonist, Nasir, a Muslim salesman from the southern city of Coimbatore.

Nasir is set within the backdrop of the scenic South Indian city, Coimbatore. The film brings us to the grass root level and gives us the opportunity to view the city eye to eye. Coimbatore’s citizens are majorly Hindu but a Muslim minority resides in the city as well.

Nasir is an observational chronicle neatly depicted through firm framework and a modulated soundscape which make the film all the more relatable. The soundscape requires a special mention formulating an evocative sense of space. It subtly marks the growth of the Hindutva politics through its auditory modulations. There isn’t a hullabaloo and ruckus of sounds but the Aazan plays in the backdrop, Ilayaraja melodies and Begum Akthar ghazals. But at the same time strong demarcations are made to mark contradictions and manipulations across the anatomy of the framework. As the plot thickens, a smooth transition from the culturally aesthetic to a soul crunching crippling moment, Nasir manages to strike the right cord with the audience. The relegation of aesthetics is what makes Nasir a phenomenal seventy-five minutes. Nasir is emphatically at the independent end of the spectrum of a gentle paced and low key affair from an area far distant. Nasir takes on an observational approach towards realism. The film begins with camera shots that show a close-up of Nasir’s community and home. This makes connects the character of Nasir(plz use italics everywhere) to the second class Indian citizen and therefore accepted. A typical Indian home is equipped with grills, shielded by layers of fabric that blanket the underlying doom within those four walls.

The film follows a self effacing Muslim in his early 40’s as he goes about his quotidian business. Nasir lives with his wife (Sudha Raghunathan) and mentally handicapped son Iqbal in a cramped apartment in a crowded ghetto of the city. Nasir is benevolent, an ideal family. A man who thinks with his heart, loves his wife dearly, protects his family, respects his religion and serves his country by being tolerant of all the ridicule and atrocities that come in his way. Nasir as a protagonist is vulnerable. In his house, gender roles aren’t black and white as though Judith Butler’s notion of gender performativity was finally at play. Nasir helps his wife in the daily chores and doesn’t play the masculinity card. He even helps his wife get dressed. The portrayal of Nasir is effortless and pragmatic. It immediately creates sympathy in the minds of the audience and in addition the disabled son who in reality has been added adds to the liberal structure. If that wasn’t enough to bring the audience be compassionate towards Nasir, the added bonus to the viewer is his lack of funds. The parade of frustrations that a lower middle class man possesses isn’t highlighted through the character of Nasir which gives him a saint like quality. Nasir toils in a busy Hindu-run sari shop where he goes about his tasks with glum professionalism. The film seems content with Nasir’s mundane activities, constant observations of his working habits on the busy lanes of Oppanakkara Street, interactions with co-workers, hobnobbing with friends, conversations customers, and his boss intermingled with Nasir’s pensive moments over beedis and chai.

A possible escape route appears through a job offer as a migrant worker in Abu Dhabi, causing him to reflect on his financial precariousness. Nasir is a relic, a man stuck in the wrong era. Nasir is your ideal 80’s hero who writes understated poetry that doesn’t see light in this commercial world, he listens to music on a tape recorder, writes loving letters to his wife who’s away from home for just three days. His skilful, sensitive and creative poetry unfortunately find an outlet in drudgery. Distinctly innocent romanticism doubles as an elaborate expository device read out as voiceover but the quietest voices make the most penetrating, memorable impact. Nasir isn’t a part of this rat race. He is unbound by his community and ceases to make a single political statement. In his mind he lives in the general anonymity of his religion. The character is what we would call a tragic hero as per Aristotle. A sympathetic blanket cloaks him as he meets an unfortunate end on being at the receiving end of unexpected mob violence. Weakening of the character makes us commiserate with his tragic end.

The Muslim community being a minority has been the target for oppression, persecution and harassment. The background noises in Nasir evoke the already audible hate stoking announcements. Nasir is a perfect Muslim character who is liberal as well as secular. He is apolitical which deems him to be weak that qualifies to be condemnation of the upper caste for his tragic end. The larger canvas of Islamophobia is brought into the picture through the lynching of Nasir. Prior to his wife leaving to visit relatives, Nasir goes along with her to drop her off at the bus station. The background is blaring with political propaganda. When we hear it from a non-biased perspective it is heard as an announcement of equalization. But in reality the duality of the message sends shackles down spines. Around Muslim dominated areas the message is of peace and harmony which depicts normalcy but as soon as they enter Hindu dominated areas the speech becomes entirely political. Otherization in Nasir hits harder due to its matter of fact portrayal. Flashback to September 2016, Coimbatore had an anti-Muslim riot, part of a wave of sectarian violence that included dozens of fatal lynching. This makes Nasir politically mute. A quiet plea of tolerance and an assertion of humanistic values during a time when such aspects cannot be taken for granted. To savour the peace in his mind and life as well as attain normalcy in a land dominated by the opposing religion. He works in a Hindu shop wherein his own boss makes no false attempt to hide his contempt for Muslims. There have been various discussions galore on the liberal potential of cinema against the prevailing injustices in the fundamental framework of society. Most of the western white audience lack proper understanding of the complex fundamental realities of the existing societal structures in India.

The viewer shares a soul with Nasir through these seventy-five minutes. Nasir undergoes tumultuous situations. The chronicle emerges through a detailed observation of his vicinity across a day of his life. This nimble romantic hopes against hope. The film beautifully captures the visual culture of the state as well as shadows the dark realities. It touches the fragile cosmopolitan of the city that disrupts with political polarization. The flashy private vehicles at a mofussil bus depot, serpentine chains of stores selling the same wares, colored decorations cutting across roads like wires all seem so meager infront of a man who keeps himself away from the brutalities of life but falls prey to viciousness.

Critics have hailed Nasir for its take on communal bigotry and reserve. The abstinence from derogatory, its relegation of the political to its margins and its refusal to give a message. Playing safe or playing smart? Nasir’s apolitical views are a virtue in itself. There seems to be no threat of political and religious violence hovering him due to his indifference. But hardly did he know

that his religion precedes him. The marginalization of the political is part of the film’s emotive substructure. One collapses without the other. Religion runs like an invisible thread embroidering life.

Nasir strolls back home at night, letter in hand, poem on his lips in a voiceover. Blink of an eye and he is attacked by a Hindu mob that kills him. So simple. A life taken within seconds over communal hatred with no fault of the deceased. Unlike usual filmmakers who would opt to keep the violence off-screen, Karthick opts otherwise. The camera is hazy and shaky as they depict the pounding of Nasir. The lynching is reduced to an indistinct blob with mere side profiles and words emerging as witness to his death. Dualities are underlined but not force-fed.

Nasir moves languidly in the direction the audience considered it would head towards yet it doesn’t feel ominous in the rising action. The bold choice to find the balance between repressing violence and perversion involved adds an extra feather to the cap of the director. But then as a community we do not understand the seriousness of situation unless there is brutality involved. A correct call by the makers to insert the ghastly details to carve a niche in the minds of the viewer is praiseworthy. The struggles of a lower middle class family, dearth of economic opportunities, the pressure one faces to migrate for better opportunities, intersectional violence on women, treatment of disabled are dire circumstances that our country faces but nothing compares to good old bloodshed to grab the attention of an Indian viewer.

The film has an abrupt resolution which casts everything that went before in a stark and moving new light. The movie urges us to sympathize with the fate of an apolitical, tolerating, poetic, non-grieving Muslim who happened to get lynched by a fanatic mob in a communal violence. Pity, tense, impactful and contemplative.

Annalise Benjamin is a freelance journalist, film enthusiast and author, Annalise Benjamin has completed her Masters in English Literature and has presented papers on ‘An Exploration of Bollywood’s Travel Genre’, ‘Goan Identity as seen in Literature and Translation’ and ‘Quest for Identity in Indian Literature’ among others. She aims to pursue her PhD. Her research interests are film studies, cultural studies, diasporic literature and transculturalism.