When I was eighteen, a dear friend, also a writer, wrote a poem for me, ripe with pulsating metaphors. I was his muse, the poem said, and he the artiste, trying to trap on paper the star-dust lying buried between my thighs and the ruby of my pomegranate lips. I was flustered, I was flattered. No one had written a poem for me before. By twenty-eight, however, having met writers and lovers who came and went, I found the once-appreciated verses wanton. I was painfully conscious of the shameful pages of history littered with insolent stories of the Pablo Picassos of this world and their deplorable treatment of the several women in their lives. Why men must only talk of a woman’s cunt and curves, I wondered. Why must the female muse always make an offering of the gift of her unclothed body to the male artiste’s imagination, for him to frolic with? Why is it that the poet and the painter cannot look beyond the quivering of my parted lips and listen (really listen) to the words that I sometimes scream, sometimes whisper, and sometimes swallow? Why are most men rather bad at writing about women?

When preparing her lecture (later published as) A Room of One’s Own, where she talks about women and fiction, Virginia Woolf visited the British Museum to study books by women. She wanted to research on two important questions: the relationship between fiction and wealth; and, the necessary conditions to produce good fiction. She had imagined that she since her questions were specific to female writers, she would find answers to them in books written by women. Much to her dismay she discovered that the walls of the British Museum were lined with books about women, not by women; all those books were written by men. Woolf noted:

Have you any notion of how many books are written about women in the course of one year? Have you any notion how many are written by men? …Sex and its nature might well attract doctors and biologists; but what was surprising and difficult of explanation was the fact that sex—woman, that is to say—also attracts agreeable essayists, light-fingered novelists, young men who have taken the M.A. degree; men who have taken no degree; men who have no apparent qualification save that they are not women.

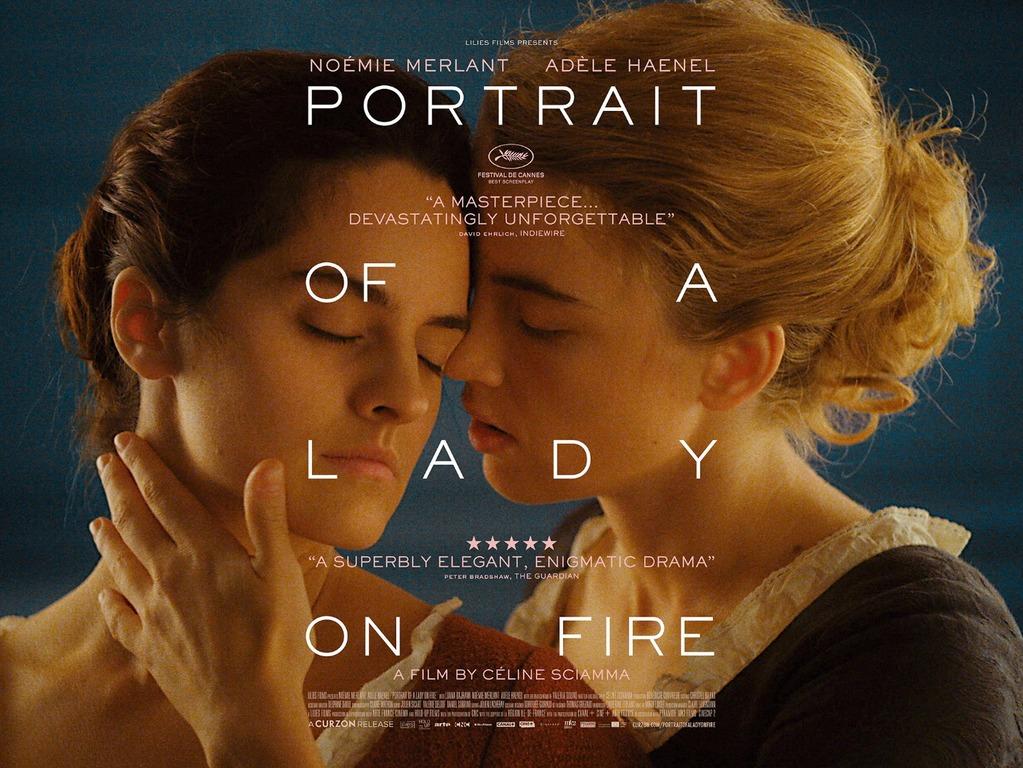

In nearly a century since Virginia Woolf’s trip to the British Museum, everything is different, and nothing is different. French screen-writer/ director Céline Sciamma’s film Portrait of a Lady on Fire (2019) is a lesson in how women can – or should – be written, painted, filmed, and talked about.

Set in the late eighteenth century, in coastal Brittany, France, cut off from the trappings of city life, Portrait of a Lady on Fire is the story of Marianne (played by NoémieMerlant) and Héloïse (played by Adèle Haenel). Marianne is commissioned by an elderly lady to paint a portrait of her daughter, Heloise. The portrait could be the eager mother and the reluctant daughter’s passport away from their suffocating life on the island, reminiscent of old gothic landscapes where people live with ghosts of the past and little promise of the future. The mother explains to Marianne what is at stake: if her daughter’s suitor from Milan takes fancy to the portrait, then their lives could change forever. However, the process of painting the portrait must be discreet, for Héloïse is unwilling to cooperate with her mother or any painter. She is hesitant to marry a stranger from a foreign, loveless land. Marianne must, therefore, pretend to be a companion to Héloïse, as she studies the features of her subject, and paints the portrait by the flickering flames of a candle-light in the dark of the night.

Noémie Merlant and Adèle Haenel are magnetic and majestic in their performances, drawing the viewer completely into their fiery world painted by the auteur’s brush in sombre, dignified, iridescent, pale pastel colours of the palette: intense blues, rich greens, burning reds, and warm blacks. Marianne and Héloïse find friendship, camaraderie, comfort, and solidarity in each other as they discover themselves within the diegetic space of the narrative. Sciamma explores the relationship between the artiste and her subject through the unfolding drama in her film. What happens when the artiste and the muse are not in an exploitative relationship? What happens when the process of creating a work of art is not distant and unidirectional, but participatory? What happens when our gaze is mutual, equal, reciprocal?

The answer lies in the magical celluloid portrait that Sciamma paints for her audience.

Portrait of a Lady on Fire is about a lot of things: the relationship between women; the dynamics of power between an artiste and the subject; female artistes leaving behind their sharp, insistent footprints in a male world; abortions and sisterhood; democratic bonds; the challenge of writing a story without a single male character;artistic conventions and their inherent gender bias (for instance, female artists, as Marianne explains in the film, weren’t allowed to paint nudes of men); heteronormative traditions and their subversion; questions of censorship and permissibility (how on-screen sex scenes between LGBTQI+ lovers and heterosexual lovers are treated by censor-boards, for instance); love, comradeship, and desire. Yet, for me, this film, most importantly, is an explosive manifesto on the exhilarating, liberating, potent, wild possibilities that are birthed when women are free to talk about themselves and their bodies, explore their limits and their potential, unchecked, give in to their urges and their needs, and learn and grow with each other in the absence of oppressive male figures and patriarchal norms.

Marianne and Héloïse unearth in themselves hot springs of love for one another. When they search and find each other, body and soul, the female film-maker does not zoom in on cleavage and clit to titillate the male cine-goer’s female on female fantasy. For Sciamma, Héloïse and Marianne’s catharsis is more urgent than their moment of sexual climax. Their love and love-making are not turned into a freakish spectacle as in Blue is the Warmest Colour(Director Abdellatif Kechiche, male) or Room in Rome (Director Julio Medem, male), or into objects of the heterosexual man’s pornographic fetish, as in Carol(Director Todd Haynes, male)or Disobedience (director Sebastián Lelio, male). Their consuming passion is not meant to be on public display – it can be, but it is not necessary, and definitely not the prescription for box-office gains or critical acclaim. The elegance with which Marianne’s painter treats Héloïse is a reflection of the respect with which the female director’s camera observes her actors. Historically, men have prescribed roles for themselves and for women and other gender minorities. Sciamma reclaims and rewrites some of these roles for herself, her actors, and her characters in Portrait of a Lady on Fire.

In her article “All cleavage and clunkiness – why can’t male authors write women?” Rhiannon Lucy Cosslett notes:

[M]ale writers do really seem to struggle to write women. …

Sometimes you come across a passage where you wonder if the writer has ever met a woman at all, or is merely using the female character he is writing as a masturbatory fantasy.

Women’s stories around the world, in different linguistic, literary, religious, and socio-economic traditions, are considered unimportant. Women are disregarded and dismissed not just by male writers/ artistes but also by readers/ viewers. Films like Portrait of a Lady on Fire can challenge these deep-set cultures of representation and consumption of women by delicately deconstructing notions of male hegemony, and initiating (visually delightful) conversations on female authority, autonomy, and agency.

Yet, under these pertinent, powerful, political layers, at its core Portrait of a Lady on Fire is simply a beautiful, moving, poignant story of two people in love, and an elegy on incandescent memories of love.

This is not a film review; just a breathless acknowledgement of the story-telling triumph that Portrait of a Lady on Fire happens to be.

The title of this article is a deliberate reference to the Twitter account @MenWriteWomen.

Bio

A fullbright scholar, Somrita is an academician, poet, translator. She has few titles in her credit.