[BEGINS]

“The night is chill; the forest bare;

Is it the wind that moaneth bleak?

There is not wind enough in the air

To move away the ringlet curl

From the lovely lady’s cheek—

There is not wind enough to twirl

The one red leaf, the last of its clan,

That dances as often as dance it can,

Hanging so light, and hanging so high,

On the topmost twig that looks up at the sky.”

Christabel

Samuel Taylor Coleridge

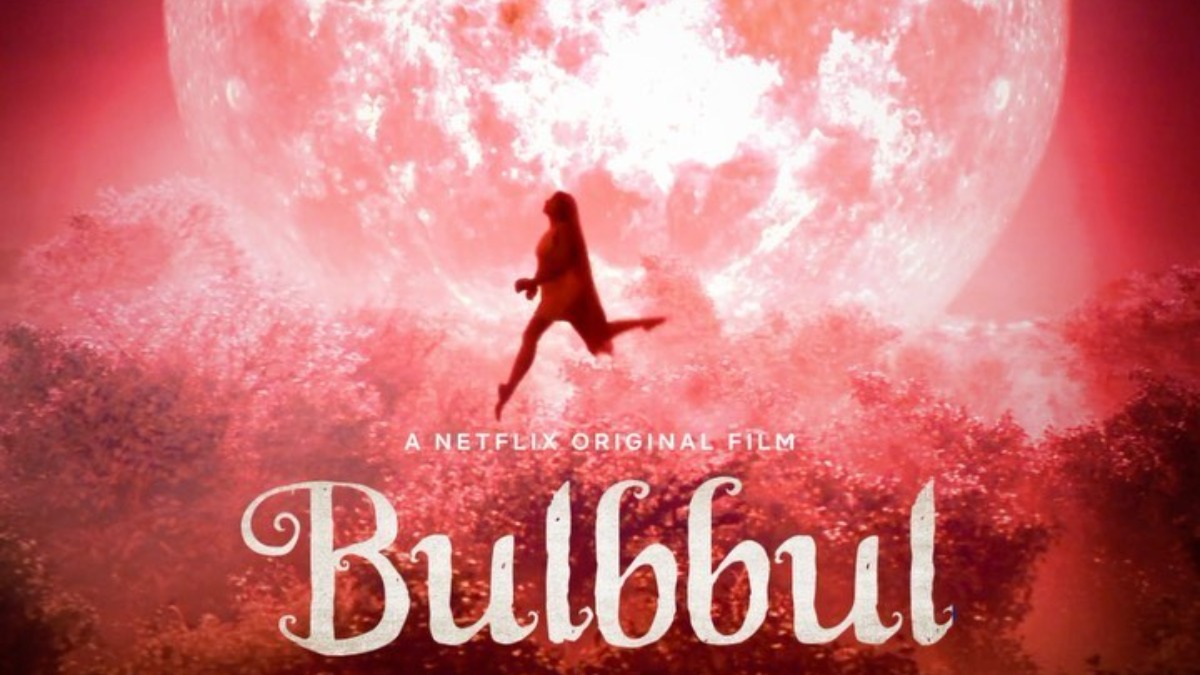

The Italian writer Elio Vittorini in a book on Gothic cathedrals once expressed a common longing for an ideal world. Gothic cathedrals, he wrote, was an intact world in which meaning is implicit. The 19th-century Romantics (Victor Hugo, François-René de Chateaubriand, Friedrich Schlegel, John Ruskin, and many others) were also deeply moved by the sight of Gothic cathedrals. The Romantics’ intense vision of the spirituality and transcendent character of the vast and soaring spaces of Gothic cathedrals has lasted to the present day. One might well imagine a sprawling haveli located at the centre of a cursed village set in 19th century Bengal presidency (1881) with a gloomy exterior but tales of lust and suppressed feelings whispering inside to become a replica of the Gothic cathedral. One can also imagine, by extension, an entire landscape under the blood moon to become a replica of the city of Hague, immortalised in <I>The Black Tulip</I> by Alexandre Dumas, with its shady park, its tall trees spreading over its Gothic houses, with its canals like large mirrors. In the context of the above observation, the Gothic drama “Bulbbul”, a Netflix original, directed by Anvita Dutt casting Tripti Dimri, Rahul Bose, Avinash Tiwary, Parambrata Chattopadhyay and Paoli Dam among others with its tale of a transformation of a revenge-seeking witch into a demon-goddess leaves an indelible impression.

But the film “Bulbbul”, with its layers and sub-layers of meanings, is more. It is an atmospheric film. It is as well a study of jealousy bordering on paranoia, lust and supressed sexuality alternating between insanity and hushed sighs rebounding within the manor, chauvinism so typical of the age, of revenge and poetic justice, the entrenched shibboleths of a hidebound society suffered by protagonists who are condemned to live within the time warp. Could the things be otherwise? Perhaps not.

It was a time when it was not just the British who did well and lived extravagantly; Bengali merchant dynasties also flourished, the like of which was the Mullick family in William Dalrymple’s<I>White Mughals</I>, for example, who had rambling baroque palaces strewn around the city, and used to travel around Calcutta in an ornate carriage drawn by two zebras. The eldest thakur scion Indranil (Rahul Bose) in the film looks like the typical Bengali patriarch of the times, to whom was married Bulbbul (Tripti Dimri), a precocious girl with a taste for scary stories, with whom the story starts as we see her hanging from a tree, She is quite savvy in climbing trees, and is as wild as a dahlia. That the five-year-old is taken as a child-bride to get married to a man years older is also part of an inverted and perverted zeitgeist.

Of the three brothers of the patriarchal family, Indranil as “Bado Thakur” taking to a child bride is suggestive of the social arrangement of a male-dominated society obsessed with savouring the female flesh and the prospect of having it well up to their elderly years. But the distortion does not end there. The marriage of Binodini (Paoli Dam), to the Mejo Thakur Mahendra (also played by Rahul Bose, Indranil’s mentally challenged twin brother), is another travesty where Binodini has only to live with all the trappings of a patriarchal social order and the pathogens if it, having to bear with her unfulfilled physical and emotional desires. Despite her age, her hierarchy as the “Mejo Bou” is another reversal as much as Bulbbul thirsting for companionship of Satya (Avinash Tiwary as “Chhoto Thakur “) who she mistook for her husband and longing for whom was her final undoing. The deliberate slaughter of a Bulbbul’s carefree girlhood, putting a ring on her toes in order to ‘control’ her and her husband wryly assuring her in due time she would understand the difference between her husband and her brother-in-law sounds like fattening a calf for future slaughter, the bridal bed serving as a metaphor for the sacrificial stake. When the little Bulbbul asks the reason for putting a ring on her toes, and knows it was a stratagem for control, she asks, “What’s control?”

A little later after the undulating journey on a palanquin, when a little Satya tells little Bulbbul the story of “chudail”, of a blood-thirsty woman with twisted feet, the shot takes us to Mahendra groping little Bulbbul and wondering what a “doll” she was and Indranil reprimanding Binodini for not being able to keep her husband in check. It is question of boundary and territory, either remaining within limits or transgressing them.

Twenty years later, when Satya is again seen coursing through a dense wood at night of blood moon creating a heady mist, Satya is told by the driver of the horse cab that the “chudail” lives here who has left a trail of murder. Satya is intrigued, as much water has flown down since he had left his little sister-in-law. Satya sees Bulbbul in charge, liberated in her easy-going way – smoking and playing a lord of the manor. Her husband has apparently left the estate. The alchemy of age and experience made her an enigmatic woman now, apparently quite unruffled by the epidemic of killings that has swept the village. Her grace is not saddled with the heirloom of her past. The flashback continues to replay happy scraps of her shared childhood with Satya, under the mango orchard, counting “1, 2, 3, 4…”

When Bulbul and Satya meet again, Bulbbul playfully asks Satya the reason of his re-emergence. Could it be that he wants to take charge of his ancestral property? We learn that Mahendra has been killed by a “demon-woman” and the widowed Binodini lives at a separate outhouse and spends life counting rosary beads, but “a litany of prayers (that) sounds like a lament” is no short of a curse. How can one, while making prayers and counting beads, curse gods in the same breath, Bulbbul asks Binodini. With the picture of Binodini turning into a widow, her vermillion effaced, head shaved, draped in starch-white saree comes the death of all her physical and emotional yearnings. When her sane brother-in-law, Bulbbul’s husband, in a brief flashback asks for little Bulbbul, when she was prattling spooky tales in a dark corner with Satya, Binodini regrets why Bulbbul was being summoned when, in all fairness, she should have been called.

Amid all this world of easy luxury draped in silk and adorned in jewels – the world of kitsch – the ugly rapists, the insane paedophiles, the chauvinist wife-beaters who invert the moral universe somehow remain outside the loop of law and justice and the royal secrets of the haveli remain hidden within its four walls. Satya holding a gun in search of a witch, the fiery embers flickering around, Bulbbul lighting candles form delicate filigrees just as the dry, scraggy branches silhouetted against the hazy, wispy sky look like a lattice made up of strips of dainty artefacts on which rests the story. And the witch-hunt – after word does the rounds of a malevolent witch killing men – begins in the tradition when it was an integral part of everyday life, touching major events such as the Reformation and the Scientific Revolution, as well as politics, law, medicine and culture. From early sorcery trials of the 14th century – associated primarily with French and Papal courts – to the witch executions of the late 18th century, there exists a corpus of literature documenting trials from Chelmsford, England, to Salem, Massachusetts and significant individuals from famous witches to the devout persecutors. The satanic witch hunts organised by the Catholic Church from the fifteenth to the eighteenth centuries (during which more than 8 million women were murdered) can be seen as a consequence of an unbridled collective shadow projection by followers of a faith dominated by a male god.

Mystery deepens when in a night swathed by the mysterious red light of blood moon, Master Dinkar, known to be a wife-beater is murdered. The hunt for the murderer is mounted by Satya with Dr Sudip (ParambrataChattopadhyay) by his side, but the trail of blood confuses as to the identity of the killer. The next morning when we see Bulbbul treated to the gentle air with a fan made of peacock-feather being waved around, she is composed and stately, casually making queries how the night of the witch-hunt went about, gingerly suggesting that the murder could well be the handiwork of not a man, but a woman. Binodini comes in from the outhouse at Satya’s suggestion. Briefly trailing back to a time when Binodini and Bulbbul shared time together, we get a glimpse of the hierarchy of power, a yet-to-be-widowed Binodini again seeking to put a toe ring on Bulbul, afraid and jealous of her free-flowing youth and its trappings. The song “KalankiniRadha” lilts in the wanton air suggestive of the inverted moral universe.

But the sleuths cannot establish evidence and murders continue apace. Satya gets suspicious of Dr Sudip, of both the murders and running liaisons with Bulbbul. A jealous Binodini plants suspicion on Satya’s mind about Dr Sudip, an act she was instrumental in doing while planting seeds of suspicion in Indranil’s mind about Satya, especially when Bulbbul’s husband pays attention to Bulbbul promising her to bring perfume for her and amorously rubbing her hands. To test if Bulbbul remains unperturbed, she tells Indranil that she has a marriage proposal for Satya.

That stratagem works. Binodini’s playful suggestion that the prospect of Satya’s marriage should first be discussed with Bulbbul, because Satya is her world and she, as it were, his trustee, rekindles the brute chauvinism in an apparently peaceable Indranil. Bulbbul gets unsettled at the prospect of Satya getting married and cries inconsolably now that she is on the verge of losing her only soulmate for ever. Rather tastily Indranil asks Bulbbul if she was not happy with the idea of Satya’s marriage. As the scene moves to the house by the side of the idyllic pond, the site where they share tales together, dullness looms large, Satya’s resolute refusal of marriage notwithstanding.

But with seeds of suspicion gnawing at Indranil and taking firm roots, the elder brother plans to send Satya to London asking him to study law and to undertake extensive travel and have fun so that London with all its charms distract him away from Bulbbul. Satya promises to paint the pond-side extension of the haveli blue. A visibly shaken Bulbul emotes, struck as she is by the thought of impending loneliness and the emotional void that she might have to face. She looks helpless and insecure and nurses a fear about losing her only emotional prop.

A furtive Indranil keeps a watch, grows suspicious when Bulbbul says that the contents of the diary were ‘personal’, disbelieving as he is of any personal space to exist in Bulbul: “nothing is personal for a married woman other than her husband”. Indranil’s atavistic voice of patriarchy can be heard. After Satya goes away, Bulbbul is emotionally shattered and distraught. And the following shots rise up to a crescendo of Bulbbul’s emotional turmoil; even as her mind thirsts for Satya’s companionship she is seen to play many roles in one body, to leaf through the pages of her diary where she co-authored spooky stories with Satya, to tear away the pages of shared authorship consigning them to flames. The glowing fire of the torn pages actually rages inside her mind. She recovers some bits of half-burnt page.

As Binodini suggests that Bulbbul must be in a state of mourning, Indranil’s mortification gets worse; he understands that he can never win the heart of Bulbbul and he has irretrievably lost the plot to Satya. His wounded manhood sniffs evidence in the scraps of burnt pages. Near the bathtub, as Bulbbul tries to come to grips with her grief by putting her inside the water, Indranil, unable to accept defeat, beats him brutally in a moment of irate rage that mauls and twists her legs. He leaves homes in a rain-washed, sullen day. And then Mahendra in a fateful night exploits Bulbbul’s vegetative state of recuperation, a sin so monstrous, that the entire village gets cursed and a blood moon takes over. The inversion of the moral universe comes through the red of the blood moon. From that time, the night of the innocent, virtuous Christabel being taken over by an evil supernatural creature disguised as Geraldine casts a spell on the entire narrative. But red often does not come with a moral imperative. Depending on the story’s needs, red can empower both a good and a bad soul. After all, both the Wicked Witch and Dorothy wore the ruby slippers. Power-hungry Sigourney Weaver wears red in “Working Girl”, and in “The Sixth Sense” the cold-blooded murderer wears it at a funeral. Warm reds (red-oranges) tend to be sensual or lusty. Perhaps, the deviousness arising out a complete reversal of the moral universe (turning red) necessitates the reification of a “chudail” into an avenging folkloric goddess.

In terms of characterisation, the real secular character in the film turns out to be Dr Sudip who, either in his capacity of administering his medical services or his capacity for quiet understanding of the real state of things shows a calibrated measure of distance and aloofness (Bulbbul calls him a coward for this). Lest he should come too close to Bulbbul, he draws boundaries, putatively crossing which Bulbbul was punished by her husband. Binodini’s brief and interspersed role is immensely complex (laudably acted by Paoli) for the focus being completely trained on Bulbbul. Binodini’s remit is to flesh out the predicament of her suppressed sexuality constantly challenged by the magnetism and fluid charm of Bulbbul (so beautifully evinced by Tripti). And Bulbbul in her turn, even after enduring the severe trauma of being beaten and violated, is as much composed as she was while undertaking her nocturnal ventures assailing the demons. The ascription of divinity on the “witch” might remind one of “Devi”. But what’s the need for the moral righteousness, one might legitimately ask.

Indranil’s jealousy for Satya, Satya’s jealousy for Dr Sudip, Binodini’s jealousy for Bulbbul, and finally Bulbbul’s jealousy for any bride that Satya might choose to take, set against Indranil and Satya’s possessive love and Mahendra’s fevered lust for Bulbbul, Bulbbul’s unexplained love first for Satya and then for Dr Sudip, Dr Sudip’s worshipful love for Bulbbul form a complicated interweft of overlapping emotions, in the maze of which lies the nether world of lust, murder and revenge leading to the final scene of epiphany. Very well crafted with the deft uses of the blood moon serving as a metaphor, the film is a poignant take on patriarchy. It is a pity that the demon-goddess does not survive the tale even in a 21st century narrative.

Bio

The writer, an occasional essayist and reviewer of books and films, had been a commentator in the edit/op-ed pages of the DNA, Telegraph, Hindustan Times, Times of India, extensively in the Deccan Herald and The Statesman during the span of last two decades. He teaches English

in a government-aided school.