Abstract

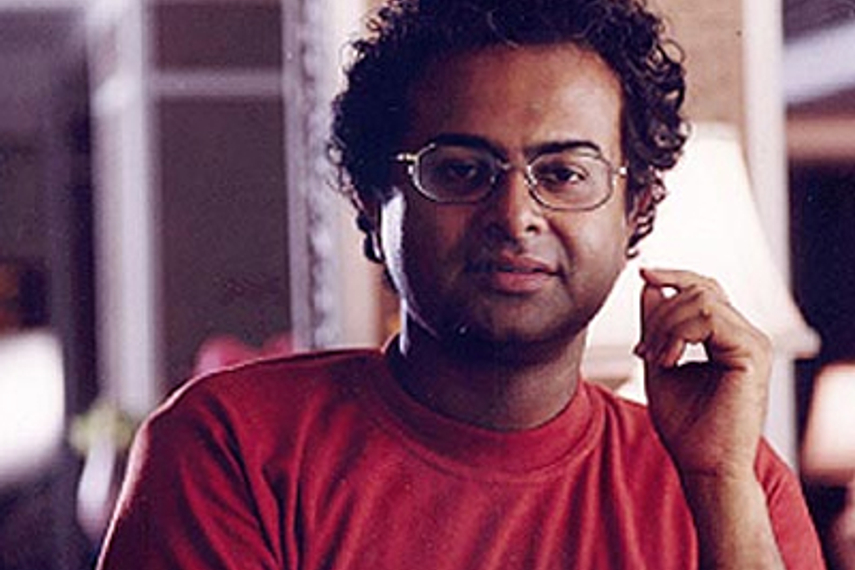

Rituparno Gosh was one of the rare film makers in India who recognized the power of silence both as a text and a narrative. Gosh made conscious efforts to communicate the music of silence in many of his films. These sincere attempts knitted the complex human desires, passions and emotions in his film. This chapter investigates the power of silence in the films of Rituparno Gosh. Here silence is not only a filmic apparatus, but also a major emotional element in his films, particularly in the portrayal of human relationship.

Key words

Silence, melodrama, sexuality, emotion

“If I have to go away, can I leave a bit of me with you?”

(An excerpt from the film ‘Memories in March’)

Introduction

The ingress of a talent like RituparnoGhosh in the film arena can be considered as a blissful coincidence to fill the possible gap that would have been left by the demise of the legendary filmmaker Satyajit Ray. It was in 1992 (the same year Ray made a sad adieu), that Ghosh made his directorial debut with ‘Hirer Angti’ (The diamond ring), a literary adaptation of a novel written by distinguished Bengali author ShirshenduMukhopadhyay. With the introduction of a new school of film making, befittingly as a successor of Ray, Ghatak and Sen, during the period of hackneyed melodrama in the 90s, Ghoshmanifested the emerging modern middle class of Bengal with visual lyric and cultural aestheticism in his creations and appeared as one of the leading figures in Bengali cinema industry to turn the apathetic viewers to the theater again. A shift from exaggerated story-telling and the reincarnation of Tagore’s music was profoundly visible in Ghosh’s cinema. The issues of the politics and expression of femininity, sexuality and the intricacies of relationships are dealt with utmost sensitivity in films like Dahan, Chitrangadaor Unishe April. But what apparently emerged as a distinctive trait of his creative notion, once travelled and tested through time and different settings became his preferred cinematic apparatus – the use of silence. Often to heighten the tension between characters or, conversely, to express the bonding between them and sometimes, as a text –Ghosh used silence as dramatic effect, similar to the concept upheldby BélaBalázs(Kulezin-Wilson, 2009).

This chapter explores how Ghosh, as a predecessor of Bengali new wave cinema, crafted silence in his films like Unishe April, Khela, Dosor, Sob choritrokalponik, Noukadubi and Chitrangada as auniquevisual language – both as narration and text. Here it will be analyzed how he defined various aspects of his characters and their stories through silence, sometimes in absolute form and at times in faint. The outline of this chapter will follow the below mentioned pattern:

- Silence as melodrama

- Silence as an element of scene composition

- Silence as an evidence of emptiness

- Silence as visual poetics

The subject will be discussed from two perspectives. One,Ghosh’s treatment to ‘silence’ in his films and the way he integrated partial soundlessness with music, especially with reference to Tagore’s compositions. Secondly, the coherence he established between silence, literary narratives and his treatment of sexuality on screen.

Ghosh – the maverick filmmaker:

To bring in a distinctive tone of cinema at a time when the industry was reprehensibly fumbling to come out of the mediocrity of commercial filmmaking, primarily decked in rustic family drama, Ghoshcontributions have been noteworthy for a number of reasons. Hisemotional approach with a strong base of film grammar, distinctive treatment to the female characters and support for liberal sexuality with a non-apologetic tone made him the pioneer of courageous cinema in Bengal that spoke about the middle class with a matchless sophistication and no inhibition(Ghose, ‘He stood for what he believed in’, 2013).

He adopted a handful of Tagore’s creations on screen, exploited the literary setting in-sync with cinema but still reserved the original sensibility intact. The cinema of Ghosh, as SaibalChatterjee wrote, “transcended the confines of region” (Chatterjee, 2013). Unlike the contemporary filmmakers he didn’t restrain his imagination within Bengal. He attempted to make his distinctive language of filmmaking acceptable to the world over the barrier of dissimilar native languages, though he didn’t compromise on the integral requirement of films over global recognition. As when he stepped outside the known periphery of regional actors and casted AiswaryaRai as Binodini in Choker Bali that certainly brought national media on his profile, but his primary reason for selecting her was due to her “’timeless’ look needed for Binodini” and “an ideal blend of the traditional and the classical”(Chatterji, 2003). Subsequently, the casting of Rai also made impact on the marketing of the film, due to her international appreciation, especially in Cannes jury. Ghosh never ignored the aspects of marketing and promotion since he started widening his spheres. Even when his films failed to secure any national or international award, fared well at the box office, due to Ghosh’swell-planned marketing activities, attributed to his years of experience in commercial advertising (Ghose, ‘He stood for what he believed in’, 2013).

As far as ideologies of his films are concerned, Issues of psychology and social construction were frequently questioned in his films. As for Unishe April, the protagonist Aditi’s formal acknowledgements to her mother (like deliberately saying ‘Thanks’) for anything and everything, signified the emotional distance she had with her mother and treated every interaction formally as a “passive-aggressive way to deal with unspoken grudge “on line with the portrayal of middle age loneliness in Bariwali(Biswas, 2013). These thematically shifts often categorize his films as artistic. The use of Jerome Stolnitz’s theory of aesthetic attitude has been apparent in his cinematic settings, especially in connection to the use of drawing room and dining table scene composition. On line withStolnitz’s assumption, Ghosh attempted to inculcate ‘sympathetic’ attitude towards the use of aesthetics in his films to guide the viewers to accept and view the setting with its own condition, devoid of their individual perception (Shelley, 2013). This not only helps the director to communicate his message to the audience with an unmatchable control of ‘auteur’, but also create a unique aesthetic language, that subsequently became Ghosh’s one of the most notable filming characteristics.

Interpreting silence: A review of silence as a language and sign

As observed by Sarah Artt, Kaplan in one of her articles discussed about “silence as a strategy” in connection to the films of Marguerite Duras and Susan Sontag. She explained in her work that silence has a multifaceted significance in cinema in relation to communicating pain or suffering, or as “a method to avoid the deception of words”. Artt wrote;

In MorvernCallar, we begin with the near total absence of sound – there is a barely discernible hum from the flashing Christmas lights, but there is no music and only the subtle sounds of Morvern‘s occasional movement as she caresses the dead body of her lover. The first wholly audible sound we discern is the tap of a keyboard as Morvern begins to read James’ suicide note. The absence of dialogue and music in this sequence adds weight to this idea of silence in relation to trauma. Not only is Morvern herself silent, she is surrounded by a silence that virtually blots out everything else – a silence that is potentially both isolating and insulating.(Artt, 2013)

The aspect of silence as sign is further discussed by Artt in light of the opening sequence in Silences of the Palace with acute silence to portray “deliberate silencing of protagonist Alia” (p. 4).

Steven G. Kellman in That Goes Without Saying: A Treaties on Silence writes about the perception of silence by lyricists like Paul Simon who considers it to be “pathological” or Joseph Mohr, who sees silence as “sacred”. He describes,

The silence of serenity is not identical with the silence of despair, any more than the silence of the lambs ought to be confused with the silence of the tapeworms or the owls. Reflecting a taxonomy of silences, the standard system of musical notation employs several different marks to punctuate the intervals between performance, including the caesura (//), general pause (-), fermata (^), and break mark (’). Silences resonate differently for us depending on age, personality, and philosophy. Renouncing speech is a way for ascetics to purge themselves of worldly impurities(Kellman, 2010).

In reference to Mike Nichols’ The Graduate Reni Celeste visualizes silence on screen in her article published in the Quarterly Review of Film and Video. In attempt of building a connection between music and silence, she explained that “If tragedy is born of music, music can be understood as a mother who delivers or permits passage for a creation autonomous from her body” and argued that music can convey more than what it is made of and holds its essence in “silence”. By reverberating the work of Robert Bresson, she writes that “sound film is what made silence possible. It was necessary to have sync sound and voices so that their interruption could allow us to probe more deeply into this mysterious thing called silence”. (Celeste, 2005).

Hence silence in films act in numerous ways according to the whims of the director. For Ghosh as well, use of silence was multi-faceted which is least possible to be replaced by dialogues.Silence in Ghosh’s film is never a complete taciturn scene, but an absence of any non-diegetic sound or a minimal diegetic sounds.

Silence as melodrama:

“All good, clean stories are melodrama,

it’s just the set of devices that determines how you show or hide it”

- BazLuhrmann(Andrew, 2001)

…And Ghosh knew that well. The futile obligation to fill the void that emerges in a scene or to intensify the ‘matters’ of expression with musical notes has been a general cinematic trend of the commercial genre. However, if seen critically, use of music has a significant connotation with cinematic realism. Despite the heightening experimentations for closer to reality and more authentic school of film making, the “position of passivity” for the commercial genre still holds true for a big part (Kulezin-Wilson, 2009). The representation of reality, can at times, leaves the audience at a state of shock and increase tension. Music is employed, broadly, to ensure uninterrupted entertainment, to reduce the “discomfort that silence induces” and to act emotionally suggestive to the audience. But silence in Ghosh’s imagination wasn’t always synonymous with anxiety. It rather acted as a catalyst to fortify the emotional intensity of a scene and acted as a bridge between the character(s) and his audience (Tichy, 2009).

In ‘Unishe April’, the second movie made by Ghosh which presumably had certain influence from Ajay Kar’sSaatPaakeBandhabut for the most part, had been inspired by Satyajit Ray’s Jalsaghar(Bakshi, I know my city can neither handle me nor ignore me: Rituparno Ghosh in conversation with Kaustav Bakshi, 2013), when Sarojini (the mother) discovers Aditi’s (her daughter) suicide note and confronts her, their ages long detachment finally finds a voice. The night reveals the threads of misunderstandings, accusations, the deep lied pain and resentment. The conversation comes to an end as the dawn breaks. Aditi asks her mother to go to sleep.Sarojini asked about the medicines that Aditi was going to take to end her life. With a frail expression Aditi assures that she won’t take them. After a moment of pause, Sarojinis still finds the pills and leaves the room. The screen fills with Aditi’s throbbing expression and the delicate sound of a morning bird outside, devoid of any external music. Aditi slowly moves towards the photo of her late father, trembling and bursts in tears. Her cry overpowers the chirp of the crow in backdrop.

If used with a musical note, the outburst of Aditi’s pain for misunderstanding her mother for so long and at the time the absence of her father, which still haunts her, wouldn’t be able to jolt the audience with same effect. As David Lopez Tichy noted, the emotional experience for the audience becomes much more factual in that moment of silence and “the audience empathizes much more profoundly with what is happening on screen.” (Tichy, 2009).The absence of music crafts a different form of sound on screen that relies more on the performance and characterization and meanings, when represented in this manner, make a deeper impact on audiences. Silence in films owes its connection to the theater, only to fill the space with dialogues and mise-en-scene(Hemmeter, 1996).

In his last released film Chitrangada – The Crowing Wish, “a film that educates without being preachy about same sex relationships”(Dasgupta, 2012), Ghoshused a dinner table sequence, with no music, barring the tick-tock of clock in the backdrop, to depict the strained relationship between the protagonist (played by himself)and his parents. The tension between Rudra and his father, who is too hesitant to come in terms with his son’s alternative sexuality,is correctly represented with the play of shadow and powerful dialogic performance of the actors. The power of such invigorating on-screen tension can create realist melodrama, when mingled with less sound effect, plays no audio cues and relies more on performances.

Silence as an element of scene composition:

“Silent cinema has an acoustic dimension that originates in the image

and can be materialized through its plastic compositions”

- Melinda Szaloky (2002)

In many of the Ghosh’s films, silence – not in the absolute form but mingled with “room tone with the addition perhaps of background noise or the foley of footsteps, cloth movements, or object handling” (Lisa Clouthardcinephile) – has been regarded as an essential ingredient for composition. Khela is one such example. When Rini (RoopaGanguly) asks Sheela, one of the main protagonists, about the reason for leaving her husband, the scene had no music playing – barring the sound of clink of the ladies’ bangles, their breathing and a mild echo of Sheela’s restrained sobbing. The concern of a friend, the discomfort of embarrassment and the ache of a failed marriage when accompanied with subjective silence composed the scene in such an aesthetical way that the entire setting, including gesture and non-existence of any noise, reflected the gloom of the protagonist’s.

While silence, as Kulezic-Wilson (2009) noted, bears connection with a feeling of fear and discomfort in a major part of the Western society, Ghosh defies such generalization and used silence or most often ‘room tone’ in his films, not to cast a shadow over the screen, but to keep the audiencehooked on to the story. He deliberately avoided the incongruity that the state of no-music triggers. The attributes of rich in taste and culture, that Ghosh’s films unfailingly presented to the theater apathetic cinema-goers in 90’s Bengal, inextricably mixed silence with the story composition in a way – different from the genre of Ray, whom he idolized –that gave birth to the new age commercial viable middle cinema or art house movies, that didn’t scare off the audiences.

In the memorial program of her late husband, Radhika in Sab CharitroKalponik ponders over her memory with the poet during the initial days of their marriage. Sitting in front of the mirror, just returned from a party, Radhika asked her husband about the reality of his woman of poetic imagination – Kajari Roy. When she said, “People keep asking me who is she? And I don’t know what to say”, the camera captures Raja from the back, standing in their veranda and smoking cigarette – preoccupied by some far-away thoughts and not answering to the question. Radhika looked at him through the mirror and asked again, “OK, at least tell me if she is me”. The poet half turned to the camera and said, “No. That’s not you”. Ghosh beautifully crafted the mystery of Kajari,a distant husband, the glint of hope in newly married Radhika and the coldness of their conjugality through the mild clink of Radhika’s jewelries encircled with the smoke of cigarette and a sore silence between them. No suggestive background score could have helped the scene to scream out loud the intricacy of their relationship in a more assertive tone. The attempt of Ghosh’s to drift his cinematic depiction between the past and surrealism, revealing the inner consciousness of Radhika to understand the essence of her husband, after he is gone, and realize that she has always been the one for him were accentuated by the rhythmic use of silence throughout the movie(Gupta, 2009).

Silence as reflector of emotion:

“The silent film has a lot of meanings. The first part of the film is comic. It represents the burlesque feel of those silent films. But I think that the second part of the film is full of tenderness and emotion”

– Pedro Almodovar(Arroyo, 2002)

Ghosh, with most of his creations, validated and espoused the statement, often as a signature style of melancholy. One of the most important prerequisites of making a good cinema is for the director to understand the power of his available tools, which connects the ‘emotional narrative’ of the film to its audiences, when employed accurately. The major criterion for most of the artistic films is the way they use silence to create a dramatic emotional ambience. Known for making films with strong emotional quotients, however, Ghosh never underestimated the significance of the aural elements. He graciously used silence and music to enhance the visual and guided his audiences through the emotional journey of the characters on screen.

Perception has long been associated with the idea of sound to demarcate the senses involved. Just like audience are dependent on the sources of sounds,in the absence of light, for understanding of our surroundings, the use of audio in movies leads the audiences’ perceptual experience. However, in cinema, other than the use of definite sound, ‘perceived silence’ is also a powerful aspect in philosophy of perception. As Sorensen (2009) asserted, “hearing silence is successful perception of an absence of sound” (p. 126). In case of Ghosh’s sequences of silence, audiences can still hear the buzz of faraway roads, hum of breathing, clink of ornaments or interiors etc. but the absence of suggestive audio cues and nonintrusive sounds create the aura of cinematic silence. As Ryan Koo (2011) rightly expressed in his article, “In a feature film, these ‘silent’ moments give the audience time to breathe; a time to sink into the picture.”

The final scene of Dosar wouldn’t have the similar impact on its viewers with any musical guidance. After the turmoil in their marriage, Kaberi gathered the courage to forgive her husband but his infidelity haunts her still. Tick-tock of the clock and an unbroken sound stream of fireflies encircled with a hum of deep sigh coming out of Kaberi, she asks Kaushik, “You haven’t smoke a cigarette in long time”. His sound of breathe breaks the bumpy silence between them and he asks, “Felt like you made love to a different person?” Another hum of sigh comes out of his wife in response, revealing her struggle to forgive betrayal. No added audio waves across the scene, except the sound of ambience. Kaushik asks, “Would you have been able to forgive me so easily if she was still alive?”Silence floats over the screen for nearly 16 seconds at a stretch. Staring deep into the blank, Kaberirecites, with a tint of impassivity, “Your lips touched mine/ though it’s not the first time/ we have kissed many a times earlier/ but it’s only now they become my shelter/ just like in the horror tales of demons and demolitions/ slowly the princess gets emaciated/ and the prince wins in the end.” Her words and expression, encircled with unyielding silence, not only manifested the epitome of strength in her characterization but also justified her decision of continuing the marriage, despite of a broken trust. Her moments of silence, sighs and the chilling yet ordinarysound of the clock augmented the intensity of the scene.

Such an emotional exposition was essential for the very theme of Dosar, which was shot in black and white to give it a gloomy outlook of a marital life, at the end leaves the audience to interpret the rest of the life of Kaberi and Kaushik. The silent aural and visual ambience (visually silence provided by the black n white) narrates the intensity of the emotions of the various characters much more than what a dialogue or musicals could generate.

Silence as visual poetics:

The cinematic appeal to the auditoryimagination is a new possibility of poetic expression,which no seriousphoto playwright can afford to neglect. “High-brow” critics and apologistsfor the spoken drama have been known to sneer at the silentdrama. Let the cinema composer[i.e., director] attune their ears to the sounding beauties of that silence. Let him create ofthis nothingnessa new form of expression, until stillness becomes eloquent and the unheard melodies sweet (Victor Oscar Freeburg, The Art of Photoplay Making, 1918)

When Gunning (2002) stated, “cinema not only records the visual appearance of past time, but the passage of time itself” that epitomize the entire century long journey of cinema and the changes it has gone through. The leap from silence to the talkies can rightly be considered as the biggest revolution in the history of cinema. However, the films of pre-talkies time never had any dearth of voice of their own in depicting the expression. Szaloky(2002) through herinvestigate of the truth behind popular saying of the academia – “silent cinema was never silent”- attempts to explain the “sounding features of “silent” cinematic images” and stated;

Early aestheticians of the cinema regarded the exclusively pictorial nature of the medium as a unique opportunity to represent the world in an unusual, unexpected, and unfamiliar (that is, artistic) way that promised to provide insight and value. The transposition of narratively significant acoustic (and other sensory) phenomena into a visual language was considered one of the prominent forms of such an artistic practice

Cinema, by foundation, is a medium that depends chiefly on the pictorial presentation of reality, where the auditory existence can only ease the impact on spectators’, but cannot influence its presence. Silence, in respect of aesthetical concept, isn’t necessarily mean to exist as a soundless vacuum, but as an “artistic means to represent reality.” Ghosh believed in the idea of treating his films as a series of “photoplay”, emphasizing more on the visual treatment to recreate reality through his quintessential camera, along with suggestive silence to make a vivid depiction for the intellectual taste of his viewers. He, although an equally strong believer of the power of music and dialogic connotation, never underestimated the significance of subjective or thematic silence. Through the use of no external audio (other than ‘ambience sound’) Ghosh attempted to illustrate a distinctive visual poetics in his films. His 2009 made film Abohoman is one of such examples.

The film opens up with the scene of the ailing director and his son in a hill station, with an unbroken hum of some faraway birds and local bees, click of camera shutter and an occasional faint echo of orchestra. Ghosh, barely on the side of using absolute non-audio, used aesthetic silence for scene composition. The connotation of cinema from the eyes of a veteran director and his encounter with the new-age film making – videography – was represented by the colossal landscape of the highland and the backdrop devoid of any suggestive music. In another scene, after the death of the film-maker, the interaction between his wife and bed-ridden mother was adorned the bell of wall clock – signifying the paradox of the incidence – where the mother, due to her old age, couldn’t be informed about the departure of her child and the wife tried to cover up the death of her husband. The silence in the scene, with the powerful dialogues and metaphorical bell of the clock, without any additional musical interpretation, created an uncanny gloom for the audiences.

Tagore keeps coming back to Ghosh’s creations both as a narrative influence and musical companion. His philosophical treatment to silenceoften starts as the endpoint or beginning of musical subtext or create the music of silence itself. The layers of grace in his films – emblematic of Tagore’s style of creation – illustrated the use of ‘room tone’, bleak melody in the backdrop or stifling silence between conversations. In Chokher Bali – Ghosh’s literary adaptation of Tagore’s novel of the same name – a truthful loyalty towards the creator’s taste was maintained all throughout the film-making, even with the use of thematic silence. When Binodini and Mahendracame close for the first time, the backdrop had only the noise of fireflies and heavy breathing of the widow’s piled up fear coated stimulation. The passion in Mahendra, drop of his stole and Binodini’s hand slowly clinging to his shoulder clearly depicted the essence of the scene. Any musical intrusion would have lowered the intensity of their intercourse and its future implication. When Tagore wrote Chokher Bali in the backdrop of colonial India, such an act of passion, between a married man and a widow, was considered as a much detested taboo. But his story never lacked the grace it required to express the emotional context of his protagonists. Ghosh followed the same tradition but with the use of added advantageous visual tools for expression. Mukherjee (2012)writes about Ghosh’s personal rendition to the Tagore’s novel, in a way that guided his audiences through the psyche of Binodini, and Ray’s influence;

The picnic scenes in Chokher Bali, in which Binodini swings and Ashalata pushes the swing, cannot fail to remind the viewer of Charu, the female lead and neglected wife of Ray’s film Charulata/The Lonely Wife (1964), based on a short story “Noshtoneer” also by Tagore, whose feet rise progressively farther from the ground as she swings. Soon after, she begins to feel the illicit love for her husband’s cousin, Amal. In a relationship in which there will be no physical consummation, Ray foreshadows for the audience Charu’s emotional and imaginative transgression through the shot of her feet leaving the solid realm of the real (2012).

When Behari received the letter Binodini wrote for him and Ashalata, lying on his table, the room displayed a mystic play of light and shadow – with a rhythmic sound of the wooden window panes and chirp of doves. He read the letter in surprise and when comprehended that she left forever, the scene filled with the sound of a bunch of doves flying away. The feeling of unexpected hollow could have never been expressed as beautifully without such metaphorical treatment. Silence, it is in theory and practice, but created a symphony of non-acoustic visual perception.

Even in Noukadubi, although considered as Ghosh’s one of the most predominantly musical films, had its moments of silence to retain the innocence of the literary text, written by Tagore. The first dinner of Ramesh and Kamala after their marriage in Calcutta or the conversation between Hemnalini and Nalinksha in Kashi was adorned with chaste silence, in the first instance to express the uneasiness of Ramesh and for the second, to indicate blooming warmth between the duos.

Ghosh and his cinema – a conclusion

Ghoshentered the industry when industry needed a talent like him to retain the glory of Tollywood,but when nobody expected, he left“like a sudden gust of wind”, after completing a remarkable docu-feature on Tagore and in the post-production of BomkeshBakshi, a popular Bengali detective novel character on cinematic adaptation. His films are particularly significant for the realistic depiction of middle-class educated family and their complicated interpersonal relationship. GoutamGhosh wrote in his article on The Times of India,

He looked at ordinary middle-class relationships from an angle that had never been explored. For example, the mother daughter relationship in ‘Unishe April’ was so refreshing, yet realistic in a society that was going through a churning. (2013)

In his dealings with the emotional trial and tribulations of Bengali middle class, the complicacy of relationships and the sense of liberation that he infused in the mind of educated cinema viewers turned him into an auteur with idiosyncratic style, not in a radical manner but with delicacy. Shamik Bag and NandiniRamnath in their article on Ghosh divided his film career in three segments – first is where he spoke of middle class aspirations and sentiments, second is his expedition in bilingual movies with national actors and third is where he came vocal about his alternative sexuality in real life and explored the issues of liberating sexualityon screen (Bag & Ramnath, 2013). However, he never shifted his core attention from loneliness and companionship in any of his films – from DahantoRaincoat. He experimented with language – spoken and cinematic – but successfully created a unique poetry on screen despite the changes. In a way that correlate with the films of Harmony Korine that challenged the commonness of principles and life but crafted a distinctive poetry through cinema (O’Connor, 2009).

Ghosh’s use silence in such an astute manner that it always lies in between the completely vocal (with diegetic and non-diegetic/metallic) and the one like artistic films of Igmar Bergman or Antonioni, that seeks to show the grave emotion of loneliness or desperation.The universality of silence is best understood by Ghosh who made this apparatus to deliver the ultimate emotion that his films as well as his characters displays reach the global audience. The silence Ghosh used in his cinema had no gender limitations, like his school of thinkingwhich was, despite the influence from Ray, more open towards portraying sexuality outside the zone of metaphor unlike the maestro (Bakshi, I know my city can neither handle me nor ignore me: Rituparno Ghosh in conversation with Kaustav Bakshi, 2013). Through the sound of ‘reality’ he expressed the trauma of his women – like in Antarmahal, the sore silence, except the chirp of pigeons in backdrop, he used in the scene where the Zamindar’s first wife thought to commit suicide for a moment, but then looked at the caged singing bird and threw away the saree lace.Ghosh preferred his scenes to speak for themselves. He preferred the exploration of alternative sexuality, like Chitrangada – The Crowing Wish, would be better defined with occasional silence – often as a respite of dialogic intercourse or musical interpretation or sometimes to swell up the sense of tension among his viewers. Even while talking about the silence in his films, his films are strongly bound on the lyrical and philosophical quality of the dialogues of his characters. Silence in Ghosh’s films always carried a definite figurative sound, just like his carefully contrived views expressed during interviews and through writing. The artist, the dreamer and the creative thinker can only be appropriately understood through his own words as he said in one of his last interviews before the untimely demise;

I identify with parts of all my films, but if I had to choose a character that was closest to my heart, it would be Binodini, played by AishwaryaRai in Chokher Bali, because she stands on the threshold of transformation. Binodini becomes a widow when widow remarriage has been legislated (by the British) but has yet to find social acceptance. There is tragic isolation in being caught in the half‐light of legitimacy. I feel a strong sense of identification with that.(Ghosh, 2012)

References

Andrew, G. (2001, September 7). BazLuhrmann (II). Retrieved July 27, 2013, from The Guardian: http://www.theguardian.com/film/2001/sep/07/2

Arroyo, J. (2002, July 31). Pedro Almodovar. Retrieved July 28, 2013, from The Guardian:http://www.theguardian.com/film/2002/jul/31/features.pedroalmodovar

Artt, S. (2013).Being Inside Her Silence: Silence and Performance in Lynne Ramsay’s MorvernCallar. Scope: An Online Journal of.

Bag, S., &Ramnath, N. (2013, May 30). RituparnoGhosh, a film-maker who pushed the envelope, dies at 49. Retrieved August 1, 2013, from Live Mint: http://www.livemint.com/Consumer/NGQP6dAn14VkftVnA3FBbL/Filmmaker-Rituparno-Ghosh-49-dies-of-cardiac-arrest.html

Bakshi, K. (2013, May). I know my city can neither handle me nor ignore me: RituparnoGhosh in conversation with KaustavBakshi. Silhouette: A Discourse on Cinema, 1-12.

Bakshi, K. (2010, January 23). RituparnoGhosh’sAbohoman: Men, Women and Love. Retrieved August 1, 2013, from Kaustav’s Arden: http://kaustavsarden.blogspot.in/2010/01/rituparno-ghoshs-abohoman-men-women-and.html

Biswas, P. (2013, May 30). An Auteur Who Never Compromised. Retrieved August 1, 2013, from Tehelka.com: http://www.tehelka.com/it-is-hard-not-to-wonder-about-the-tangible-ordinariness-of-death-in-ghoshs-films/

Celeste, R. (2005). The Sound of Silence: Film Music and Lament. Retrieved August 1, 2013, from Cine Monkeys: http://www.cinemonkeys.com/reni/silence.html

Chatterjee, S. (2013, May 30). A gutsy filmmaker whose craft transcended the confines of region. Retrieved August 1, 2013, from The Hindu: http://www.thehindu.com/news/national/other-states/a-gutsy-filmmaker-whose-craft-transcended-the-confines-of-region/article4765457.ece

Chatterji, S. A. (2003, July 6). ‘Chokher Bali will widen my horizon’. Retrieved August 1, 2013, from The Times of India: http://articles.timesofindia.indiatimes.com/2003-07-06/news-interviews/27178157_1_aishwarya-rai-rabindranath-tagore-tagore-novel

Dasgupta, P. (2012, September 2). Chitrangada – The Crowning Wish. India.

Deosthalee, D. (2011, August). Of Marriage and Morals.Retrieved August 1, 2013, from Film Impressions – Independent_Informed_In-depth:http://www.filmimpressions.com/home/2011/08/dvd-review-dosar-the-companion.html

Freeburg, V. O. (1918). The art of photoplay making. New York: The Macmillan.

Ghose, G. (2013, May 31). ‘He stood for what he believed in’. Retrieved August 1, 2013, from The Hindu: http://www.thehindu.com/news/national/he-stood-for-what-he-believed-in/article4766772.ece

Ghose, G. (2013, May 31). RituparnoGhosh: A trailblazer for a new generation. Retrieved August 1, 2013, from The Times of India: http://articles.timesofindia.indiatimes.com/2013-05-31/india/39655113_1_rituparno-ghosh-best-filmmaker-research-scholar

Ghosh, S. (2012, December 01). I Get Respect Even When I’m The Target of Homophobia. Retrieved August 01, 2013, from Marie Claire: http://www.marieclaireindia.com/article.aspx?artid=283704

Gunning, T. (2002, February).Making Sense of Film. Retrieved July 27, 2013, from History Matters: The U.S. Survey on the Web: http://historymatters.gmu.edu/mse/film/film.pdf

Gupta, P. D. (2009, September 3). ShobCharitraKalponik: The lost poem in the jungle. Retrieved August1 1, 2013, from SE7EN MM: http://se7enmm.blogspot.in/2009/09/shob-charitra-kalponik-lost-poem-i…

Hemmeter, T. (1996).Hitchcock’s Melodramatic Silence. JSTOR, 32-40.

Kellman, S. G. (2010). That goes without saying: a treatise on silence. Puerto Del Sol .

Koo, R. (2011, November 3). Music vs. Silence: 5 Simple Rules for a Better Film. Retrieved July 27, 2013, from No Film School:http://nofilmschool.com/2011/03/music-silence-5-simple-rules-film/

Kulezin-Wilson, D. (2009). The Music of Film Silence. JSTOR, 1-10.

Mukherjee, S. (2012).Chokher Bali: a historic-cultural translation of Tagore. Retrieved August 1, 2013, from Jump Cut: A Review of Contemporary Media: http://www.ejumpcut.org/currentissue/MukherjeeChokerBali/text.html

O’Connor, T. A. (2009). Genre-Ing: Harmony Korine’s Cinema Of Poetry. Wide Screen.

Shelley, J. (2013). The Concept of the Aesthetic. Retrieved August 1, 2013, from The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy: http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/aesthetic-concept/#AesAtt

Sorensen, R. (2009). Hearing silence: The perception and introspection of absences. In M. Nudds, & C. O’Callaghan (Eds.), Sounds and Perception: new philosophical essays (pp. 126-146). USA: Oxford University Press.

Szaloky, M. (2002).Sounding Images in Silent Film: Visual Acoustics in Murnau’sSunrise.JSTOR, 109-131.

Tichy, D. L. (2009, April 8). The critical importance of silence in film scoring.Retrieved July 28, 2013, from David Lopez Tichy Twenty-First Century American Composer.http://davidtichy.com/47/the-critical-importance-of-silence-in-film-scoring/

AUTHORS’ Biography

Dr. Sony Jalarajan Raj is Assistant Professor at the Department of Communication, MacEwan University, Edmonton, Canada. Dr. Raj is a professional journalist turned academic who has worked in different demanding positions as reporter, special correspondent and producer in several news media channels like BBC, NDTV, Doordarshan, AIR, and Asianet News. Dr Raj served as the Graduate Coordinator and Assistant Professor of Communication Arts at the Institute for Communication, Entertainment and Media at St. Thomas University Florida, USA. He was full time faculty member in Journalism, Mass Communication, and Media Studies at Monash University, Australia, Curtin University, Mahatma Gandhi University and University of Kerala. He is a three times winner of the Monash University PVC Award for excellence in teaching and learning. Dr Raj has been in the editorial board of five major international research journals and he edits the Journal of Media Watch. Dr Raj was the recipient of Reuters Fellowship and is a Thomson Foundation (UK) Fellow in Television Studies with the Commonwealth Broadcasting Association Scholarship. Dr. Raj has extensively published his research works in high impact international research journals, edited books.

Contact Details

Dr Sony Jalarajan Raj, Assistant Professor, Faculty of Fine Arts & Communication, MacEwan University, 7-166C City Centre Campus 10700 104 Avenue NW, Edmonton, AB T5J 4S2 , Canada.

Tel: 001-780-633-3594(O)

Cell: 001- 587-778-2426

Email: [email protected], [email protected]

Ms. Rohini Sreekumarsuccessfully completed and defended her PhD from the School of Arts & Social Sciences at Monash University, Australia. In her doctoral thesis, Rohini explores the visual culture and receptional practices of Indian cinema among global nations. She had her Master’s Degree in Mass Communication and Journalism from Mahatma Gandhi University, India with a gold medal and first rank. Rohini is the recipient of National Merit Scholarship and Junior Research Fellowship from the University Grants Commission of India. Her research interest includes Indian film studies, Malayalam cinema, Journalism Practice, Mediated Public Sphere and Diaspora Studies.

Contact Details:

Tel: 00601116326460 Email: [email protected], [email protected]

Mr. NithinKalorth is the Assistant Professor at Amity University, India. He is also pursuing his PhD from the School of Social Sciences in Mahatma Gandhi University, India. Nithin has earned his post-graduation from the University of Madras with first rank and gold medal in Electronic Media. Nithin is the recipient of National Merit Scholarship and Junior Research Fellowship from the University Grants Commission of India. Nithins’ research interests include South Indian film studies, digital photography, social and political documentary, democratization of visual media, public sphere and social media. His doctoral thesis investigates on Tamil new wave cinema and its epistemology. Apart from his research, Nithin does regular lecturing as visiting faculty at Indian Institute of Management, Kozhikode, Punjab Technical University, Indian Institute of Management, Bharathiyar University, and University of Calicut. Apart from his academic ventures, Nithin is actively involved in documentary film making and digital photography projects. His few documentary films were screened at various international and national short film festivals and campus festivals of India.

Contact Details

Cell Phone: +91-8891008303 Email: [email protected]