I saw my first Indian film in 1956 in the USA. It was, unsurprisingly, Satyajit Ray’s Pather Panchali(Rhymes Along the Road, 1955), an international art house hit. Soon I saw Aparajito (The Unvanquished, 1956), Ray’s second film, the middle of his trilogy on the life of young Apu as he grows to adulthood.In Paris in 1987 a week of Indian New Wave Films included Kumar Shahani’s Māyā Darpan (Mirror of Illusion, 1972), on a young woman’s isolation following India’s 1947 Independence.

At the Cannes International Film Festival in 1975 there was M.S. Sathyu’s Garam Hāwā (Scorching Wind, 1975), on the question for Muslims at Independence–to emigrate to newly created ‘Muslim’ Pakistan, or remain Indian. I’d already covered film festivals in San Francisco, West Berlin, Locarno, Barcelona and Venice. In Tunis, or Carthage 1977, a female Algerian film buyer and I saw Bharathiraja’s 16 Vayathiniley (Age 16, 1977), a rural girl pregnant by an urban veterinarian, consoled by a lame village boy (Kamal Hasan). “I’m overworked,” the buyer later said in Algiers.

Avoiding Paris winters, in North Africa, I found I couldn’t understand Middle Eastern cinema without India. So I travelled overland.In Rabat, along the way, I covered a Mediterranean Film Festival, in Tunis an African-Arab one, in Istanbul Balkan and in Tehran international, the last complete with a retrospective of Iranian cinema–truly the last pre-revolution one.

In Beirut I stumbled into a Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) camp while looking for the PLO Film Office, in Aleppo I was called “Yahūdi” (‘Jew’; I’m Christian/Buddhist), in a taxi. In Kabul I met two new film directors. (Pearson 1981a/1982a/1983a), just before the USSR took over. I bused through Pakistan, towards New Delhi, arriving via train 1974/1975 at the International Film Festival one day after New Year’s, India’s first such festival in a turbulent decade. (Poduval 2014) I met Ray again had met Ray in Tunis, again in Tehran. He particularly liked Miloš Forman’s One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975) for its sympathetic treatment of mental illness, a difficult thing to accomplish, he thought. I liked it from my own experience as a ward attendant in the same hospital, Forman for his metaphor for communist Czechoslovakia.

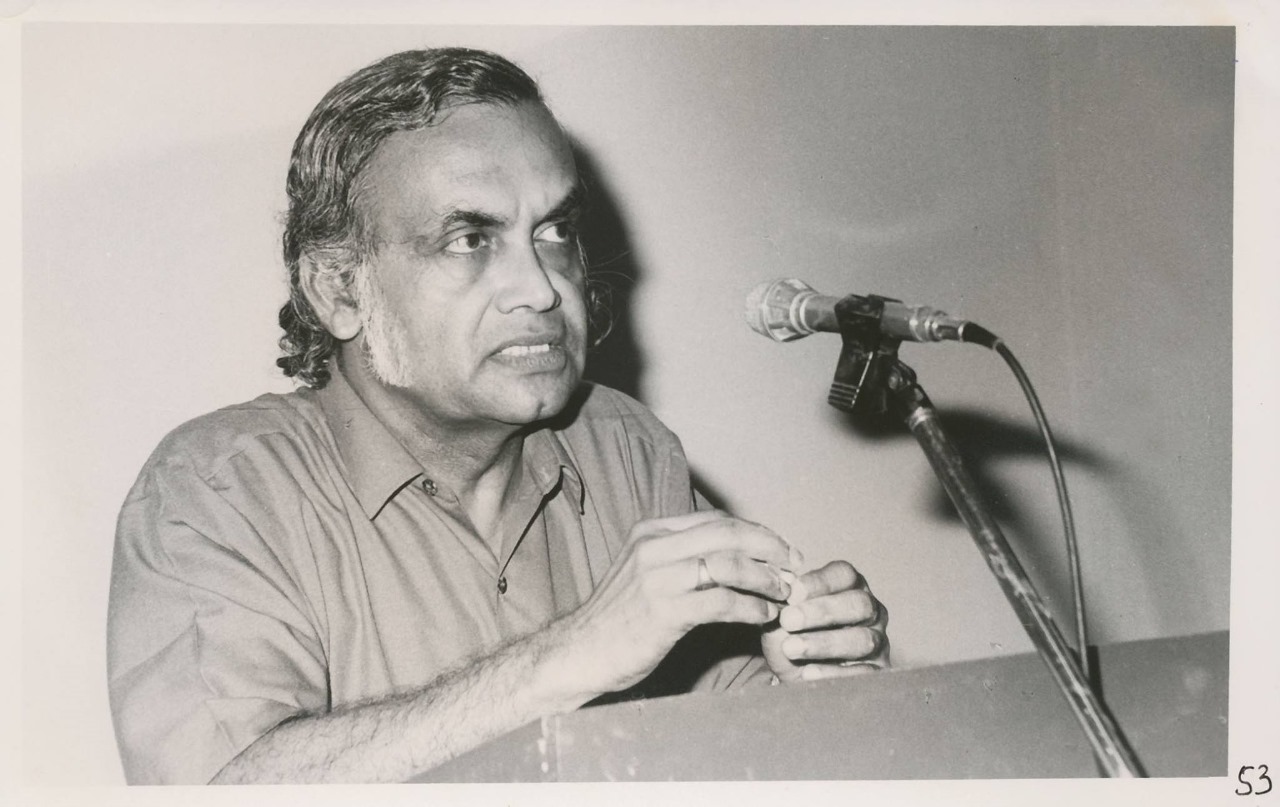

When I did reach New Delhi, in 1975, Jagat Murari, former head of the Film and TV Institute of India (FTII) in Poona (now Pune), now international festival director, suggested I meet Mr. Paramesh Krishnan (for short, P.K.) Nair, head of the National Film Archive of India (NFAI), also in Poona. Mr. Nair hadn’t founded the NFAI, but had been at its inauguration a decade before. During that decade he’d scrounged silent Indian films from late directors’ cowsheds, 35-year old sound classics came from the defunct Prabhat Studio, now the FTII studios. His quest for old films continued.

Following Indian sojourns by Jean Renoir (Ray 1976), Marie Seton (Seton 1971, revised 2003), and the new Federation of Film Societies of India (FFSI), Nair made film academic. He opened a film appreciation course, preserved memorabilia, created a Film History, and inspired better film journalism (Baskaran 2024).Nair knew Indian cinema better than anyone, past or present. I knew some cinema in countries I had left behind. We greeted each other “like brothers or two peas in a pod” (Pearson, letter 2016). If I’d been a reel of film, I’d still be in a temperature-controlled vault, referred to when needed.

I saw many Indian classics, including the first extant, D.G. Phalke’s Raja Harischandra (1913, or its 1917 re-make), on an unlucky mythological king. In V. Damle and S. Fatelal’s Sant Turkaram (1936), the 17th-century Marathi dalit (“oppressed,” literally; below the four named Hindu castes) saint denied his own poems, has them returned by divine intervention i.e. running the film backwards. Kumar Shahani (1980) compares the simplicity the simplicity of the film to Charlie Chaplin: “It would be suicidal to attempt the naive quality of Sant Tukaram” today,” and technically with SF-VFX etc available, “The transformation of subject matter itself into form and content is hardly ever possible…I do not know if, in most cases, the aspiration itself is dangerous.”

To Nair, myth and cinema are almost the same, if not so theoretical. Take off your shoes before entering the FTII auditorium; no eating allowed. (There are rumours he was Christian.) He took notes during films and had a Wanted List of lost films. I couldn’t keep up with his note-taking, but wrote on Japanese film (1975a), lectured on African film and typed up lists of Arabian, Albanian and Afghan films (1975b, 1979).

The next time I saw Satyajit Ray, after my first trip to Poona, he wanted to test my knowledge of Indian cinema. “Have you seen Damle and Fatelal’s Sant Dnyaneshwar [1940], Sant Sakhu [1941],” and lowering his already baritone, “Sant Tukaram?”

“Yes, I have,” I said, of Sant Tukaram.

“That’s where a study of Indian cinema should begin,” said Ray.

I’d seen several Hindi films in North Africa, in Algiers S.S. Vasan’s Chandralekha (a name, The Girl Like a Moon, 1948) dubbed into Arabic, its fabulous drum dance intact. In Cairo, Dev Anand’s anti- hippie-hit Hare Rama Hare Krishna (1971), with hippy (Amherst 2010) Zeenat Aman, gyrating to its eponymous hit song, and poor subtitles. Many other Hindi films seemed to feature somebody named Helen.

In Poona, at the FTII auditorium across from the NFAI, I saw more Ray. I learned Raj Kapoor re-did a scene from his own Awārā (Vagabond, 1951) in his teen-romance Bobby (1973), the film made to recoup the loss from his circus-spectacular Merā Nām Joker (I Am a Clown, 1970)–the nearest India had yet come to Fellini.One evening a week there were classic Hindi films. I found Vijay Bhatt’s Baiju Bawra (Crazy Baiju, 1952) “very Indian and very good,” and Nasir Hussain’s Tumsa Nahin Dekha (I’ve Seen Nobody Like You, 1957) exhilarating.

I found quintessentially Indian, Sagar Sarhadi’s dialogue in Basu Bhattacharya’s Anubhav (Experience, 1971). Unknowingly guesting his wife’s former boyfriend, Sanjeev Kumar is told by wife Tanuja: “He never touched me. He never had to.” This could be to Devraj (ed. 2017), “Divine ecstasy.”Bhattacharya then homaged Roman Polanski’s Knife in the Water (1962), possibly from a dupe–another Nair specialty. In Bhattacharya’s Aavishkār (Discovery, 1974) Rajesh Khanna tells his intended (Sharmila Tagore) “Before marriage Love can be spiritual” and “Time doesn’t pass. We do.”

Kumar Shahani, Mani Kaul (Gangar 2024), Adoor Gopalakrishnan, and John Abraham, early new wave directors, who studied partly under the FTII’s Wisdom Tree with Ritwik Ghatak, graduated from FTII in that last decade. Ghatak, an erratic drunkard, but a master theorist and director, suffered from the “deep gashing wound” that was the Partition (Dasgupta 2004), also the subject of Sathyu’s Garam Hāwā. Ghatak’s Ajantrik (Manuel, the titular automobile, 1952), made three years before Ray’s Pather Panchali, had never been released. His four subsequent films had found critical but no commercial success. To Ray, who admired him, Ghatak “only subject was the Partition.” Thrown out of India’s Communist Party as a Trotskyite, he was a maverick. His time at the FTII had been short, yet unique and influential.

Saeed Mirza, Girish Kasaravalli, newer new wave directors, still students at the FTII, retained Ghatak’s influence. One day Kaul revisited, encouraging students on dorm front-steps, India’s poor wire infrastructure would fade as ‘wireless’ progressed. (See Sing 2024; Rajadhyaksha 2003). This was proving true–I’d first heard Laxmikant–Pyarelal-Anand Bakshi’s Main shāyar to nahin (I’m not otherwise a poet) from Bobby on a battery-operated audiocassette player in Afghanistan.

A week of Italian films came through the FTII, with no subtitles. I was given the task of para-dubbing. With English script in hand, a microphone in front of me, I recited dialogue in English. The trick is to speak after a character speaks, not while s/he speaks. One evening Nair Sahib held up a screening of a French documentary until I could arrive from an evening Ganapati puja [Elephant-god ceremony] to translate” the documentary. (Pearson 1979)

Nair Sahib wanted to acquire an Andy Warhol film, any Andy Warhol film. I recommended Paul Morrissey’s Warhol-produced Heat (1972): “It’s based on [Billy Wilder’s 1950] Sunset Blvd.”

I lent Nair my copy of underground cartoonist Robert Crumb’s special issue of Zap (1968) comix. Nair asked to keep it. It may now be in the Nair Archive at the Film Heritage Foundation in Mumbai. My copy of Amos Vogel’s Film as a Subversive Art (1974), a favourite, may also be there. The reels of censor cuts, deposited at the archive, were shown late at night, drawing large audiences. The foreign films were the best.

I met Film Historians Amrit Gangar and Theodore Baskaran. Decades later, Amrit invited me to an annual Charlie Chaplin festival in Adipur, in the Raan of Kutch, Gujarat. Theodore dedicated to me The Story of a Movie Mogul: S.S. Vasan (2020), the founder of Gemini Studio in Madras (now Chennai) and director-producer of Chandralekha. Neither the trip nor the dedication would have happened if I hadn’t known Nair Sahib. Also at the NFAI I met Eric Barnouw, and in Madras (now Chennai) S. Krishnaswamy, co-authors of the seminal Indian Film (1963, revised 1980). Barnouw was researching a third edition, but died before completion. Krishnaswamy has the manuscript.

At local theatres I saw Ms. Aman again, wet-wiggling to Laxmikant-Pyarelal’s hit “Hai hai yeh majbori” (You, You Helpless [actually sung by Lata Mangeshkar]) in Manoj Kumar’s Roti Kapadā aur Makān (Bread, Clothing, and House, 1974), an all-star deluxe epos on poverty and joblessness. Mythology (e.g. wet saris ogled by Krishna) certainly is “intercalated” in Hindi films (Derné, 1995), as is Hindu ritual (Lutgendorf 2014). Yet I saw a remarkably un-Sanskritic adult comedy, Hrishikesh Mukherjee’s Chupke Chupke(Stealthily, 1975), remade from Agradoot’s Bengali Chadmabeshi (Disguised, 1971). At night, in bed with his wife (Sharmila Tagore, unseen), Parimal (‘Sweet Smelling’ i.e. Dharmendra), turns off a light with his bare foot. At a morning show I caught Shyam Benegal’s Ankur (Seedling, 1974), neither deluxe nor funny, on feudal exploitation and the price paid by the poor. It seeded Benegal’s career, somewhere between Mukherjee’s middle-wave and New Wave cinema: his Manthan (The Churning, 1978) was actually financed by Rs. 2 (2 cent) donations from 500,000 members of a dairy co-operative.

I saw the low-budget devotional-super-hit, Vijay Sharma’s Jai Santoshi Mā (Hail Mother-goddess of Satisfaction, 1975). In spite of the efforts of half the Hindu pantheon, the narrative needs no such intervention, unlike that of the 1936 Sant Tukaram. Shunned by her jealous sisters-in-law, her husband gone astray, a bride achieves satisfaction only when he returns with enough cash for a new home. Much has been written on Jai Santoshi Mā by Philip Lutgendorf (2002, 2014).This was the decade of writers Salim (Khan) and Javed (Akhtar) and their subaltern Angry Young Man Amitabh Bachchan (Kazmi 1998), defining the masala (mixed spice) film, defying decades of social and political unrest; and also of Rajashri producers’ Amol Palaker, the middle-class Affable Young Man (Poduval 2014).

I saw much Bachchan scripted by S&J and by others. In one S&J collaboration, a villain shoos away frolicking young women from his bedroom to tend to more villainy. One sticks her head through a curtain, and asks, “Shaam ko? (This evening?)” It was the first line I ever understood in a Hindi film. It became a meme for me, as did many S&J lines for India: “Main aaj bhi phenke hue paise nahi uthata” (Chaudhuri 2015) translates to “Today I don’t pick up money thrown at my feet.”

In Yash Chopra’s Deewar (Wall, 1975), S&J and Amit’s second hit, after Zanjeer (Chain, 1973), a smuggling-don (gold out, consumer goods in) he is pitted brother against his brother (Shashi Kapoor), a policeman, under a bridge, where Nikhat Kazmi (1996) allegorizes the turmoil of their mā (mother) with Indira Gandhi’s India, the family, the nation. Two S&J scripts later, an upper-class family (knives and forks on tablecloths in fancy hotels) replaced social turmoil with patriarchal revenge, during Moraji Desai’s term as Prime Minister.I saw Basu Chatterjee’s Chitchor (Thief of Hearts, 1976) four times, mainly for one song, Ravindra Jain’s Gori Tera Gaon Budda Pyār (Fair-skinned Girl, Your Village is So Lovely). Actor Amol Palekar, an overseer mistaken for an engineer, a possible husband for a village belle, and now her music teacher, sings first of love for a village, then for her (Zarina Wahab).

I wrote five articles for the then best Indian film magazine, Filmfare, the first on Italian director Pier Palo Pasolini, then the 1963 Urdu musical romance, Harnam Singh Rawail’s Mere Mehboob (1963, My Beloved) (Pearson, 1975c, 1975e).

Nair recommended a week of Guru Dutt’s masterworks at another local theater; my third Filmfare article compared Dutt’s Kāgaz ke Phool (Paper Flowers, 1959) to Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane (1941) (Pearson 1975d).

The films I saw at the FTII Mr. Nair told me about. The films I saw commercially, I told Nair about. He became my unofficial guru/mentor, I became his unofficial vidyarthi/student.

One evening, as he, I, and a scenarist strolled across the FTII grounds, I said, “I see a lot of Shakespeare in Indian cinema.” The scenarist scoffed, mumbling “Romeo and Juliet.” He was one step ahead of me. Yet, Will is found in Urdu historicals, comedies of errors, Hamlets, shrews and moneylenders (Gangar 2019, Verma 2005). Sohrab Modi, director and star of Khoon ka Khoon (Filial Murder, 1935), India’s first talkie Hamlet, now lost), recites “Hath Not a Jew eyes?” from The Merchant of Venice (c. 1597, 3:1 60-76), now under Roman oppression in Bimal Roy’s 1958 Yahūdi.

Another evening, Nair screened a pristine print of Bert Stern and Aram Avakian’s Jazz on a Summer’s Day(1959), newly acquired from a disappointed distributor in Kerala. The distributor, said Nair, probably bought it, thinking it titillating. The poster’s tagline, after all, was “…love on a summer’s night,” with the critical quote (undoubtedly false) “Embarrassingly Intimate” near a nuzzling couple. JoaSD, however, is a documentary on the 1958 Newport (RI) Jazz Festival. Most cutaways are to a yacht race.

I had seen JoaSD before so I knew what to expect–well-shot-edited jazz performances by Thelonious Monk, Anita O’Day, Louis Armstrong and other greats. I sat near the back of the FTII auditorium with two students for most of the film, but near the end I moved up and sat by Nair Sahib. At midnight on that summer’s day, on a screen in Poona, gospel singer Mahalia Jackson sang “The Lord’s Prayer.”

As the lights went up, Mr. Nair said, “This must have been a big hit.”

“No,” I answered. “It’s an art film. It only played specialty houses.”

I was lucky to see this pristine print of JoaSD, newly acquired by the NFAI, before it faded. In 2012, Nair told me the print had probably deteriorated, as he doubted that the NFAI, now run by bureaucrats, had kept it cool. (JoaSD was restored in 4K only in 2021.)

There were political problems, but I didn’t know much about them yet. Finally, the National Congress Party split. Instead of contesting a case against her use of government vehicles at an election rally, Prime Minister Indira declared an official government ‘Emergency’ nationwide. Opposition politicians were jailed, press muzzled, politics censored from new films. Both turmoil and freedom decreased (Patra and Ray eds. 2025). Security was installed at the FTII gate. I, a non-official student, could no longer enter. No more Indian film classics or censor cuts for me.

I remember Nair and I, that day, standing together in the NFAI garden, looking at the sunset with double sadness. It was the day I had to leave the NFAI. More importantly, it was the day Ritwik Ghatak died.

***************

Now I had to roam the ends of India in third-class railcars, without reservations, to explore its cinematic treasures, on my own. My “alternative home was nowhere and everywhere,” like Amitabh’s absentee father Anandbabu after ratting on his fellow smuggling Bombay dockworkers, riding the rails (unseen) in Yash Chopra’s S&J-scripted Deewar (Joshi 2014). Helen, the provocative dancer, kept popping up not in my dreams, but on the big screen. Having little to do with any plot, according to one wag, she was often “quickly dispatched” (See Pinto 2006).

In Bangalore I met Nair again, at a festival called Nostalgia. Nair Sahib had supplied the films. There, I saw the first Hindi film of Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay’s novel, P.C. Barua’s Devdas (a name, Disciple, 1935) “perhaps the first Indian film to break the hitherto box-office monopoly on happy endings,” to Nair (2017). Avatars of Devdas, to Nandal (2017), or knockoffs, followed “until the Devdas film-within-a-film” in Dutt’s Kāgaz ke Phool, with Dutt now as a failing filmmaker. I too felt like Devdas, rejected, riding the rails (See Bhabha PMLA X:1). Bhabha quotes Adela in Forster’s A Passage to India, “In space things touch, in time things part.” Borders remain, time departs. Nair Sahib recommended I meet, the father of Sri Lankan cinema Lester James Peries, and in Bangladesh filmmaker-journalist Alamagir Kabir.

So I travelled South Asia, discovering other regional and national cinemas. I had seen several Indian New Wave films at FTII, now I was seeing first releases and reporting back to Nair. I discovered Gujarati mythologicals, Malayali realism (Radhakrishnan 2014), collapsing Tamil studios (Pillai 2014) as K. Balachander escaped to shoot his Apoorava Raagangal (Rare Melodies, or Conflicting Ragas, 1975) in actual homes; Telugu retreads (Devulapalli 2024 21-29); a not always friendly rivalry between Ray, Mrinal Sen, and critic Chidananda Das Gupta in Calcutta (Basua and Dasgupta ed. 1992); in neighboring Sri Lanka Lester’s rural humanism, in Bangladesh Alamgir’s urban militancy (Kabir 1969), and more Hindi hit rip-offs (Filmfare, 1978).

At a biannual national government film festival, each time in a different city, I saw Nair in Bombay (Mumbai), but not Madras (Chennai) or Calcutta (Kolkata). Directly or indirectly though, through Nair, I met even more film historians: Satish Bahadur, Randor Guy, Chidananda Das Gupta and Shivendra Singh Dungarpur. Dungarpur in 2017 released a documentary feature on Nair Sahib, Celluloid Man, through his Film Heritage Foundation.

Through Ray, I also met Ray’s first biographer, Marie Seton. Ray hadn’t liked her book: “She should have talked more to me” (See Seton, revised 2003).

****************

“Indian Bengali and Punjabi cinema had declined, shorn [upon Indian Independence in 1947] of half its audience [as well as] Islam, as a religious base” (Pearson 1979-1985). This was the “deep gashing wound” Ghatak suffered, considered in Sathyu’s Garam Hāwā. Now, in 1974, Pakistan had split in two, its east wing now Bangladesh.

I crossed into Bangladesh to refresh my visa, meet Kabir, and see and write on Ghatak’s penultimate Titash Ekti Nidar Nām (A River Named Titash, 1973). (Filmfare 1976).I crossed into Pakistan to refresh my visa several times, the last while a military coup crippled the film industry and killed its film societies (Ahmed January 1 1979, Pearson June 16 1976).

The one time I did let my visa lapse I spent 10 days in New Delhi’s Tihar Jail. After I was released, and Indira’s Emergency over, at the next New Delhi Festival I introduced myself to Anand Patwardhan, who had shot Prisoners of Conscience (1978), a documentary on political prisoners in Tihar, at about the time I was there. I told Patwardhan my story, but it hardly resonated. His documentary was about political prisoners, not a silly foreigner who’d let his visa lapse. Patwardhan has continued to expose governments, superstition, corruption, and poverty in his documentaries. His latest, Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam (The World Is Family, 2023), is partly old home videos.

So, who could I identify with? I was alone. There was Amitabh as a Christian in Manmohan Desai’s Amar Akbar Anthony (1977), one of three lost souls, brothers actually, raised in different religions. But not Amitabh as scripted by S&J in in Ramesh Sippy’s Sholay (Flames, 1975), a Sergio Leone-curry/spaghetti Western, where he dies like Gary Cooper in Sam Wood’s 1943 For Whom the Bell Tolls, despite me fighting a queue to see him. Nor, with Amitabh’s Sholay prison-found/life-partner ‘hot’ ‘Garam Dharam (Bhattacharya 186),’ i.e. Dharmendra.

Their duet “Yeh dosti nahin todenge” (This friendship will never end, lyric by Anand Bakshi) seemed not for me, although their S&J dialogue was heard everywhere on loudspeakers. Banished, where did I belong? An academy? No, not yet. I rode unreserved, sleeping in cheap hotels, hostels, and fire stations. Not a terrorist, a dacoit, or a spy, how could this happen to me? (See Lal 1998) My location of culture was not a barāta (procession), but a suitcase, of filmi memories–song-booklets, newspaper clippings, and hand-written notes.

No film was completely “incomprehensible” (Metz, quoted in Ghelawat 2010 76) in my ‘Third Space’ (Bhaba 1994 39), certainly not Bachchans’. As Susan Neiman re-paraphrases Georg Simmel, sometimes “strangers can hear and understand things that native observers tend to miss” (Neiman 2024).

Nair Sahib had been my fulcrum, my touchstone. Now I was halfway between Amol (‘riches’) and Anand (‘Peace’) or nearly. I just didn’t know it yet.

**************

By 1979 it was time to go “home,” to the USA. On my way, in Paris I bought a copy of Pariscope, the city’s weekly entertainment guide. “Deko (Look),” I startled, ‘a festival of classic Third World films, many from India, running across the river Seine!” Several of the films I had seen at FTII. I dove into the Paris Metro and came up at the right station. Festival director Galeshka Moraviof told me, “There is someone from India in Paris now, for a UNESCO conference, you may know–a Mr. P.K. Nair.

“He was my best friend in India.” Later I’d say he was my best friend in the world.

“He’ll be at the theatre in about an hour.”

That evening with Nair, I saw Guru Dutt’s, Pyāsā (Thirst, 1957) for the third time, on a poet who, like Tukaram, has his work taken from him in Calcutta–from a balcony in Paris!

In the next two weeks Nair and I visited two film archives, one on the Paris outskirts, the other the overwhelming if disorganized Cinémathèque française. Its founder, Nair’s mentor Henri Langlois, who also advised me before I headed east, had passed away, so we saw his second in command, Mary Meerson.

Nair had first flown to Paris in 1968, delivering 50 films from the NFAI to the first “Panorama of Indian Cinema” in the West. (Garga 1968) Now it was time to ask Meerson for some European films in return. Nair knew he’d never receive them: the Cf was too disorganized. Jean Rouch, the semi-documentary director who worked primarily in Africa, told Nair the government was waiting for Meerson to pass on, to claim and organize the holdings. Ironic this was, as in 1968 the national government’s attempt to take control of the Cf had in part set off riots across France, in that year of nearly universal radicalism (Lee & Shailain 1985 212).

Langlois had been Nair’s guru, as Nair was mine, but Nair was not acerbic, as was Langlois. In Dungarpur’s documentary Celluloid Man, there is a clip of Langlois on a telephone, the French not subtitled, avoiding someone he didn’t want to hear: “Mr. Langlois isn’t here right now. But if you call this evening, I’m sure he will be.” Nair would never have done that–he was too nice of a guy.

Whenever we encountered anyone who didn’t speak English, I translated French to English. We visited Guy Hennebelle, the most prominent critic of Third World Cinema. His wife and collaborator, Monique Martineau, asked if we’d mind eating beef. We didn’t mind. We visited Nasreen Muni Kabir in her attic apartment, and an Iranian haute bourgeois who, having escaped the recent Iranian revolution, knew to keep a low profile.

Nair wanted to see the one new film in Paris likely to never be seen in India, Dušan Makavejev’s SweetMovie (1974), a politics-sex satire partly shot in Amsterdam. Makavejev follows psychologist Wilhelm Reich, who integrated Freud and Marx, fully releasing libidos, or “orgone energy,” to cure (even) cancer. Reich’s steel-lined “orgone accumulators,” human-fitted boxes, could concentrate those libidos. Again Nair and I sat in a balcony, and I translated the French subtitles, to the amusement of a woman sitting next to us.

A week later we both left Paris, Nair for Pune, and I for Seattle. A half-dozen of us stood together as Nair stepped toward his Air France jet. I spontaneously stepped forward. Nair Sahib stepped toward me. We said our personal goodbyes. I knew I wouldn’t see him for years, perhaps decades, but I felt I would see him again.

***************

Home in Bellingham WA (USA), I wrote a (still unpublished) history of Indian film, up to 1979. In the 1980s, before the internet, Nair Sahib and I exchanged notes via those little blue aerogrammes. I remember quoting Arnold Schwarzenegger in one, “I’ll be back”). Or I’d telephone him. In 1997, he informed me, “India now has a lesbian film, [Deepa Mehta’s Indian/Canadian] Fire.”

“Oh, we have the same thing on TV. It’s [a sit-com] called Ellen,” I said.

“It’s part of globalization,” quipped Nair.

I laughed. It was true. It was the 1990s. (See Rajadhyaksha 2003 37-38)

***************

I did not see India again until 2011, 32 years later. Unreserved was too crowded, so I traveled Second Class.

India, low on investment funds in 1991, had liberalized its import economy. The British Marks and Spencer consumer chain, previously in standalone stores with little to sell, now sold high fashion in fancy malls. McDonalds, KFC, Dairy Queen and internet cafes dotted urban landscapes.

Plus, money flew in from the diaspora, from engineers in Los Angeles into Telugu film, from Seattle Microsofters into Kanarese film, from diasporic tycoons in the Gulf into Malayalam film. Standalone cinemas dwindled, multiplexes multiplied like Apples and Amazon. I soon learned to fly, mostly on Indigo Airlines. From below, I could see satellite dishes rising from slums.

But my first stop was of course Pune. Nair had retired, was widowed, diabetic, and run-down by a motorcycle. He walked with the aid of a Konkani mahari (housemaid), Sushma. She’d get mad because we’d chat and not eat until midnight. Once I swear I heard her grumble, “Son of a b**ch,” but she couldn’t have, because she didn’t speak English. Still, she called me Uncle.

Nair Sahib had not returned to his hometown, Trivandrum, in Kerala after retirement, but stayed, now in an apartment, near the NFAI. I had mailed him several boxes of annual catalogs from Seattle International Film Festivals. They arrived soaked in rain. Indian Customs had stacked them outside during the 2011 monsoon.

We embraced. He invited me to stay with him, and from then on whenever I was in Pune, I did. He also was going blind, so I would see new Indian movies, tell him about them, and he would give me his insights. He still saw some films at NFAI and at the newly created Pune International Film Festival (PIFF). We saw several films at PIFF together. There were by now international film festivals in every major city, every year, across the country, even Jaipur, Nasik et al.

With Sushma we were invited to a three-day seminar on film study at Whistling Woods, a new, privately owned film institute in the middle of Mumbai’s new Film City. For the second time I Q&A’d, Vishal Bhardwaj, the director of three Hindi Shakespeare films, Maqbool (Macbeth, 2004) in Mumbai, Omkara (Othello, 2006) in rural U.P, and Haider (Hamlet, 2014) in Kashmir. Primarily he is a composer (See Bhardwaj/Kotru 2024 494-504); he’d cut some army violence against the Kashniri insurgence from Haider, knowing the government would if he didn’t; he had Khurram (Claudius) maimed rather than killed, his legs amputated by goddess-like Kali avenger Ghazalka’s (Gertrude’s) suicide vest, to Bhardwaj a fate worse than death (Vats 2014, Bhardwaj 2015). The Kali myth adds agency to Gertrude/Ghazalka, saving her only son, Haider, as well as Kashmir. (Trivedi 2019) In Hamlet something is “rotten” in the state of Denmark (1600 1:4:90). In Haider, the Indian army should be more rotten than it now appears.

After two years as Nair’s guest, whenever I was in Pune, Gangar told me Nair and he, during their evenings together, would each have a nightcap. So, my evenings with Nair became a bit more animated, if shorter. We didn’t always agree, just like Siskel and Ebert. He called one film I liked “corny,” but liked my description of Juan Estelrich’s Spanish Bombay Goa Express (2014). On the way to Goa a travel writer shares a first-class train compartment with a beautiful woman. It is a fantasy. It was perhaps the last film we discussed.

The last film Nair and I saw together was a documentary on Frederico Fellini. Again, I translated French subtitles, this time to the annoyance of male PIFF spectators around us.

I videotaped Nair, with a drink in his hand he shouldn’t have had. A scene from the tape ends Devraj’s Introduction, in Yesterday’s Films for Tomorrow (2017), on Nair’s “favorite moments on screen.” He “picked two…a bead of sweat hanging from the nose of an oblivious ektara player” from S. Sukhdev’s India ’67 (1967) and from a foreign film, the torturing of a scorpion by children at the beginning of Henri-Georges Clouzot’s Le Salaire de la Peur (The Wages of Fear, 1953)–a scene not in the NFAI print. Perhaps it was now a censor cut.

Nair was planning to shift back to Trivandrum with all of his film memorabilia (DVDs, books, magazines, catalogs) to set up a trust, so anyone could have access to it. He didn’t want to gift it to the NFAI because, now run by bureaucrats, he (probably rightly) thought it would just be dumped in a room somewhere. (David Farris, an American I met in Bangalore, tells me the NFAI refused Shyam Benegal’s offer of his own original materials.)

“May I work in that trust?” I asked Nair.

“Yes,” he’d responded. But it was too late.

I was in Bangalore, at another film festival, when I learned Nair Sahib, my mentor/guru/friend, had passed away 4 March 2016. I wish I had been with him. I miss telling him about any film I have just seen, new or old, to gain his insights. Before Nair Sahib died, filmmaker Vidhu Vinod Chopra had offered to transport him to Mumbai for the best medical care. “No,” said Nair Sahib, “use that money to preserve films.”

Because he died before moving, there is no trust. The Film Heritage Foundation has all his memorabilia. The Heritage and I are in contact, but I’ll probably never see that Zap or Amos Vogel’s Film As a Subversive Art again.

In a 2007 interview by Aurofilm, on “what happens to most of our filmmakers from developing countries,” Nair Sahib recalled:

…first one or two films are wonderful then

…big money comes with strings attached

…they lose their identity

…they cater to the world market instead of their local things

…okay they’re making smart films

…but individual talent you know is something

…money should be given to an artist if you believe he’s an artist

…don’t keep on peeping over the shoulder

…if you’re interfering with that kind of filmmaker, you can’t expect them to toe your line

…let them make the films they want to make then only great films will come out.

(Aurofilm, Kerala International Film Festival, in Devraj ed.)

**********

My time with Nair in Paris was a highpoint in my life. As Vladimir in Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot (a play in which I played Vladimir) says to his friend Estragon, after helping up two other characters from the ground (I am now paraphrasing), “For that one moment we were needed,” verbally justifying their existence. I can’t think of anything I’d rather do again than translate for Nair Sahib in Paris. If he wasn’t my guru, I told him several times, he was my best friend in the world. Having known him, and the NFAI, can justify my existence.

“In space things touch, in time things part.” (Forster)

“Time doesn’t pass, we do.” (Sarhadi)

“The space-time co-ordinates of the diegetic world become legible only through the affective intervention of the politically radical viewer” (Radhakrishnan 97).

I miss Nair Sahib.

As does everything else he archived. My ‘suitcase’ of Indian filmi memories is now archived at the University of Washington’s Suzzallo Library, Seattle WA, USA.

************

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

My gratitude to my readers, Carol Slingo, Randy Allred, Theodore Baskaran, Amrit Gangar and Sudhir Mahadevan (University of Washington, Seattle).

My humble respect to Priya Joshi and Rajender Dudrah, editors of The 1970s and its Legacies in India’s Cinemas. Several of their contributors, listed in my Bibliography, jogged and even augmented my memory.

My more recent respect to Nirupama Kotru and Shantanu Ray Chaudhuri, editors of The Swinging ’70s:Stars, Style and Substance in Hindi Cinema. Several of their contributors altered and footnoted my sentences, just before publication. The book, always worth looking into, is a compendia of 1970s filmi academia and nostalgia.

My forthcoming respect to Parichay Patra and Dibyakusum Ray, editors of Cinema and the Indian National Emergency: Histories and Afterlives. This 2025 volume will undoubtedly shed more light on India’s cinema and politics of the turbulent 1970s.

But, most of all, my undying respect to the late Mr. P.K. Nair, former director of the NFAI (National Film Archive of India), my guru, and my host in Pune in his later years. Little of this paper could have been written without him.

************

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Ahmed, Zubai. (1 January 1979) Letter. National Film Development Corporation Limited, Pakistan Institute for the Study of Film Art

- Armbrust, Walter. “The Ubiquitous Nonpresence of India: Peripheral Visions from Egyptian Popular Culture, in Gopi and Moorti eds. 200-204

- Aurofilm. (2007) “An Interview with Mr. P.K. Nair former Curator of the National film archives of India.” Trivandrum: Kerala International Film Festival, in Dharaj ed.

- Barnouw, Eric and S. Krishnaswamy. Indian Film. Columbia (NY): Columbia University Press

- ________. (revised 1980) Indian Film. Oxford: Oxford University Press

- Baskaran, S. Theodore. (2024) Email. Bangalore

- ________. (2020) The Story of a Movie Mogul: S.S. Vasan. Chennai: Indian Universities Press

- Basu, Saki and Shuvendu Dasgupta eds. (1992) Film Polemics. Calcutta: Cine Club of Calcutta

- Beckett, Samuel. (1952) Waiting for Godot, originally in French as En attendant Godot. New York (NY): Grove Press (1964 reprint)

- Bhabha, Homi K. (January 1998) “On the Irremovable Strangeness of Being Different,” PMLA (Publications of the Modern Language Association of America). Germantown (NY): Modern Language Association of America

- Bhardwaj, Vishal. (2015) Haider (Hamlet, the script). Noida (UP): Harper Collins Publishers

- ________. (2015) Maqbool (Macbeth, the script). Noida (UP): Harper Collins Publishers

- ________. (2015) Omkara (Othello, the script). Noida (UP): Harper Collins Publishers

- ________, interviewed by Nirupama Kotru. (2024) “I Came to the Industry Because of Gulzar Sa’ab’: Memories of Cinema in the Seventies,” in Kotru and Chaudhuri eds. 494-504

- Bhattacharya, Roshmila. (2024) “Dharmendra: He-Man and the Master of the Universe,” in Kotru and Chaudhuri eds. 181-190

- Burt, Richard. (2003) “Shakespeare and Asia in Diasporic Cinemas: Spin-offs and citations of the plays from Bollywood to Hollywood,” in Richard Burt and Lynda Bose eds. 265-303

- Burt, Richard and Lynda Bose eds. (2003) Shakespeare the Movie II. New York (NY): Routledge

- Chaudhuri, Diptakirti. (2015) Written by Salim-Javed: The Story of Hindi Cinema’s Greatest Screenwriters. Penguin India

- Crumb, Robert. (1968) Snatch (comix, a special of Zap comix). San Francisco (CA): Apex Novelties

- Dasgupta, Shyama. (19/12/2014) “A Bottle in One Pocket and Your Childhood in the Other: Ritwik Ghatak’s Bombay-Poona Years.” Bombay: Film Heritage Foundation

- Derné, Steve. (1995) “Market Forces at Work: Religious Themes in Commercial Hindi Films,” in Media and the Transformation of Religion in South Asia, eds. Lawrence A Babb and Susan S. Wadley. Philadelphia (PA): University of Pennsylvania Press, pp. 191-216

- Devulapalli, Krishna Shastri. (2024) “North by South-East: How We Found Bombay in Madras,” in Kotru and Chaudhuri eds. 21-29

- Dungarpur, Shivendra Singh. Film Heritage Foundation. Mumbai: filmheritagefoundation.co.in

- Forster, E.M. (1924) A Passage to India. New York (NY); Harcourt Brace, and Co.

- Gangar, Amrit (2024) Email. Mumbai

- ______. (2019) “The Indian ‘Silent’ Shakespeare,” in Trivedi and Chakravarti eds.

- ______. (2024) “The Seventies: Hindi Cinema’s Defining Decade: Eloquence of Extremes, Rigour of Fresher Forms,” in Kotru and Chaudhrui eds. 390-402

- Garga, D.B. (1968) Pour Servir de Base a Une Histoire du Cinema, un Initiation au cinema indian. Paris: Cinémathèque française

- Gehlawat, Ajay. (2010) Reframing Bollywood. New Delhi: Sage Publications Pvt. Ltd.

- Gopal, Sangita and Sujata Moorti eds. (2010) Global Bollywood: Travels of Hindi Song and Dance. New Delhi: Orient Blackswan Private Limited

- Joshi, Priya. (2015) Bollywood’s India. New York (NY): Columbia University Press

- ______. (2014) “Cinema as Family Romance,” in Joshi and Dudrah eds. 8-22

- ______. (2014) “WORKING NOTE: From Ceiling fans to A/C and juice: Javed Akhtar in conversation with Priya Joshi,” in Joshi and Dudrah eds. 136-139

- ______ and Rajinder Dudrah eds. (2014) The 1970s and its Legacies in India’s Cinemas. London: Routledge

- Kabir, Alamgir. (1969). The Cinema of Pakistan. Dacca: Sandhani Publications

- Kazmi, Fareeduddin. (1998) “How angry is the Angry Young Man? ‘Rebellion’ in Conventional Hindi Films,” in Nandy ed. 134-156

- Kazmi, Nikhat. (1996) Ire in the Soul: Bollywood’s Angry Years. New Delhi: Harper Collins

- Kotru, Nirupama and Shantanu Ray Chaudhrui eds. The Swinging ’70s: Stars, Style and Substance in Hindi Cinema. Bengaluru: Om Books International

- Lal, Vinay. (1998) “The impossibility of the outsider in modern Hindi Film,’ in Nandy ed. 228-259

- Lee, Martin A. and Bruce Shlain (1985). Acid Dreams: The CIA, LSD and the Sixties Rebellion. New York (NY): Grove Press

- Lutgendorf, Philip. (2002) “A Superhit Goddess/A Made-to-Satisfaction Goddess: Jai Santoshi Ma,” in Manushi, a Journal About Women and Society 26-34

- _______. (2014) “Ritual Reverb: Two ‘blockbuster’ Hindi Films,” in Joshi and Dudrah eds. 62-75

- Mandal, Antara Nanda. (1 April 2017) “‘Yesterday’s Films for Tomorrow’–PK Nair’s Writings on Cinema to be Launched,” Cinema and Allied Art Forms. New Delhi: Silhouette Magazine

- Nair, P.K. Yesterday’s Films for Tomorrow, Rajesh Devraj ed. (2017) Mumbai: Film Heritage Foundation

- Nandy, Ashis ed. (1998) The Secret Politics of Our Desires: Innocence, Culpability and Indian Popular Cinema. New Delhi: Oxford University Press

- Neiman, Susan. (June 6 2024) “Fanon the Universalist,” in New York Review of Books 19

- Patra, Parichay and Dibyakusum Ray eds. (forthcoming: 2025) Cinema and the Indian National Emergency: Histories and Afterlives. New Delhi: Bloomsbury Publishing India Pvt. Ltd.

- Pearson, Lyle. (1981-83) “Afghanistan.” London: International Film Guide, 1981a 49-50; 1982a 51; 1983a 57-58

- ______. (1975b) AFRICAN AND ARAB FILMS to see or to buy: A checklist prepared for the National Film Archive of India. Poona: unpublished

- ______. (1975a) “Calm Without, Fire Within,” Festival of Japanese Films 11-16 October. Poona: NFAI, Chitrajali Film Society

- ______. (1979-1985) A Geography of Indian Cinema. Bellingham (WA): unpublished manuscript

- ______. (1975d) “Guru Dutt: The Typical Hero Tag Doesn’t Fit,” in Filmfare 24:25, 32-33

- ______. (1975e) “Mere Mehboob: Heroine Vanishes Into the Woodwork,” in Filmfare 24:23 18-19

- ______. (1975d) “Pasolini,” an obituary, in Filmfare n.d.

- _______. (16 June 1979) “Porn and Politics in Pak Films,” in Youth Times. New Delhi:32-33

- _______. (2016) “Revelling [sic] in the Impress that India’s Archivist of Flickering Images Left Behind:” Lyle Pearson remembers his friend P.K. Nair, film archivist and film scholar and founder of the National Film Archive.” New Delhi: The Wire

- _______. (1968) Shakespeare on Film: A Survey. San Francisco (CA): San Francisco State College

- _______. (1979) “Some Films Recommended for Indian Film Festivals…from The Third Balkan Film Festival Istanbul 1979 to The Third World Festival.” Paris: unpublished

- _______. (1978) “The Style is Strictly Bombay,” in Filmfare 26:26 14-16

- _______. (1976) “Titash Ekti Nadir Naam: Astonishingly beautiful images pass like the boats…,” in Filmfare 27:4 42-43.

- Pillai, Swarnavel Eswaran. (2014) “Tamil cinema and the post-classical turn,” in Joshi and Dudrah eds. 76-89

- Pinto, Jerry. (2006) Helen: The Life and Times of a Bollywood H-bomb. Mumbai: Penguin

- Poduval, Satish. (2014) “The affable young man: Civility, desire and the making of a middle-class cinema in the 1970s,” in Joshi and Dudrah eds. 36-49

- Radhakrishnan, Ratheesh. (2014) “Aesthetic Dislocations: A re-make of Malayalam Cinema of the 1970s,” in Joshi and Dudrah eds. 89-100

- Rajadhyaksha, Ashish. (January 2003) “The’Bollywoodization’of the Indian cinema: cultural nationalism in a global arena,” in Inter-Asia Cultural Studies 4:1. 25-39 Oxford: Routledge

- Ray, Satyajit. (1976) Our Films Their Films. Westport (CT): Hyperion

- Seton, Marie. (1971, revised 2003) Portrait of a Director: Satyajit Ray. New Delhi: Penguin

- Shahani, Kumar. (January 1980) “The Saint Poets of Prabhat,” in Filmworld 197-202. Bombay:T.M. Ramamachandra; also in Shahani, Ashish Rajadhyakasha ed., in Further Reading. 188-191

- Trivedi, Poonam and Dennis Bartholomeusz eds. (2006) India’s Shakespeare: Tradition, Interpretation and Performance. New Delhi: Pearson Education in South Asia

- ________ and Paromita Chakravarti eds. (2019) Shakespeare and Indian Cinemas: Local Habitations. New York (NY): Routledge

- ________. (2019) “Woman as Avenger: ‘Indianising’ the Shakespearean Tragic in the Films of Vishal Bhardwaj, in Trivedi and Chakravarti eds. 23-44

- Vats, Vaibhav. (27 October 2014) “Kashmiri ‘Hamlet’ Stirs Rage in India,” New York Times

- Verma, Rajiva. (2005) “Shakespeare in Hindi Cinema,” in Trivedi and Bartholomeusz Ed. New Delhi: Pearson Education in South Asia

- Vogel, Amos. (1974) Film as a Subversive Art. New York (NY): Random House

- Watave, Bapu. (1985) V. Damle and S. Fattel: A Monograph. Pune: National Film Archive of India

- FILMOGRAPHY

- Ajantrik (Manuel, 1952). d: Ritwik Ghatak

- Amar Akbar Anthony (1977). d: Manmohan Desai

- Ankur (The Seedling, 1974). d: Shyam Benegal

- Anubhav (Experience, 1971). d: Basu Bhattacharya

- Aparajito (The Unvanquished, 1956). d: Satyajit Ray

- Apoorava Raagangal (Rare Melodies, or Conflicting Ragas, 1975). d: K. Balachander

- Avishkār (Discovery, 1974). d: Basu Bhattacharya

- Awārā (Vagabond, 1951). d: Raj Kapoor

- Baiju Bawra (Crazy Baiju, 1952). d: Vijay Bhatt

- Bobby (1973). d: Raj Kapoor

- Celluloid Man (2012). d: Shivendra Singh Dungarpur

- Chandralekha (1948). d: S.S. Vasan

- Chhadmabeshi (Disguised, 1971). d: Agradoot (a collective)

- Chitchor (Thief of Hearts, 1976). d: Basu Chatterjee

- Citizen Kane (1941). d: Orson Welles

- Deewar (Wall, 1975). d: Yash Chopra

- Devdas (Disciple, 1935). d: P.C. Barua

- Ellen (30 April 1997). “The Puppy Episode.” Season 4, episodes 22/23d d: Gil Junger. Los Angeles (CA): ABC TV

- Fire (1996). d: Deepa Mehta

- Garam Hāwā (Scorching Wind, 1975). d: M.S. Sathyu

- Hari Rama Hare Krishna (1971). d: Dev Anand

- Haider (Hamlet, 2014). d: Vishal Bhardwaj

- Heat (1972). d: Paul Morrissey

- Jazz on a Summer Day (1959). d: Bert Stern, Aram Avakian.

- Jai Santoshi Ma (Hail Mother-goddess of Satisfaction, 1975). d: Vijay Sharma

- Kāgaz ke Phool (Paper Flowers, 1959). d: Guru Dutt

- Khoon ka Khoon (Filial Murder [Hamlet], 1935). d: Sohrab Modi

- Knife in the Water (1962). d: Roman Polanski

- Maqbool (Macbeth, 2004). d: Vishal Bhardwaj

- Māyā Darpan (Mirror of Illusion, 1972). d: Kumar Shahani

- Merā Nām Joker (I Am a Clown, 1970). d: Raj Kapoor

- Mere Mehboob (My Beloved, 1963). d: Harnam Singh Rawail

- Omkara (Othello, 2006). d: Vishal Bhardwaj

- One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975). d: Miloš Forman

- Pather Panchali (Rhymes Along the Road, 1955). d: Satyajit Ray

- Prisoners of Conscience (1978). d: Anand Patwardhan

- Pyāsā (Thrist, 1957) d: Guru Dutt

- Raja Harischandra (1913 or 1917). d: D.G. Phalke

- Roti Kapadā aur Makān (Bread, Clothing, and House, 1974). d. Manoj Kumar

- Le Salaire de la Peur (The Wages of Fear, 1953). d: Henri-Georges Clouzot

- Sant Dnyaneshwar (Saint Dnyaneshwar, 1940). d: V. Damle and S. Fattelal

- Sant Sakhu (Saint Saku, 1940). d: V. Damle and S. Fattelal

- Sant Tukuram (Saint Tukuram, 1936) d: V. Damle and S. Fattelal

- Sholay (Flames, 1975). d: Ramesh Sippy

- Sunset Blvd (1950). d: Billy Wilder

- Sweet Movie (1974). d: Dušan Makavejev

- Titash Ekti Nidar Nām (A River Named Titash, 1973). d: Ritwick Ghatak

- Tumsa Nahin Dekha (I’ve Seen Nobody Like You, 1957) d: Nasir Hussain

- Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam (The World Is a Family, 2023). d: Anand Patwardhan

- Yahūdi (Jew, 1958) d: Bimal Roy

(Photo courtesy: National Film Archive of India)