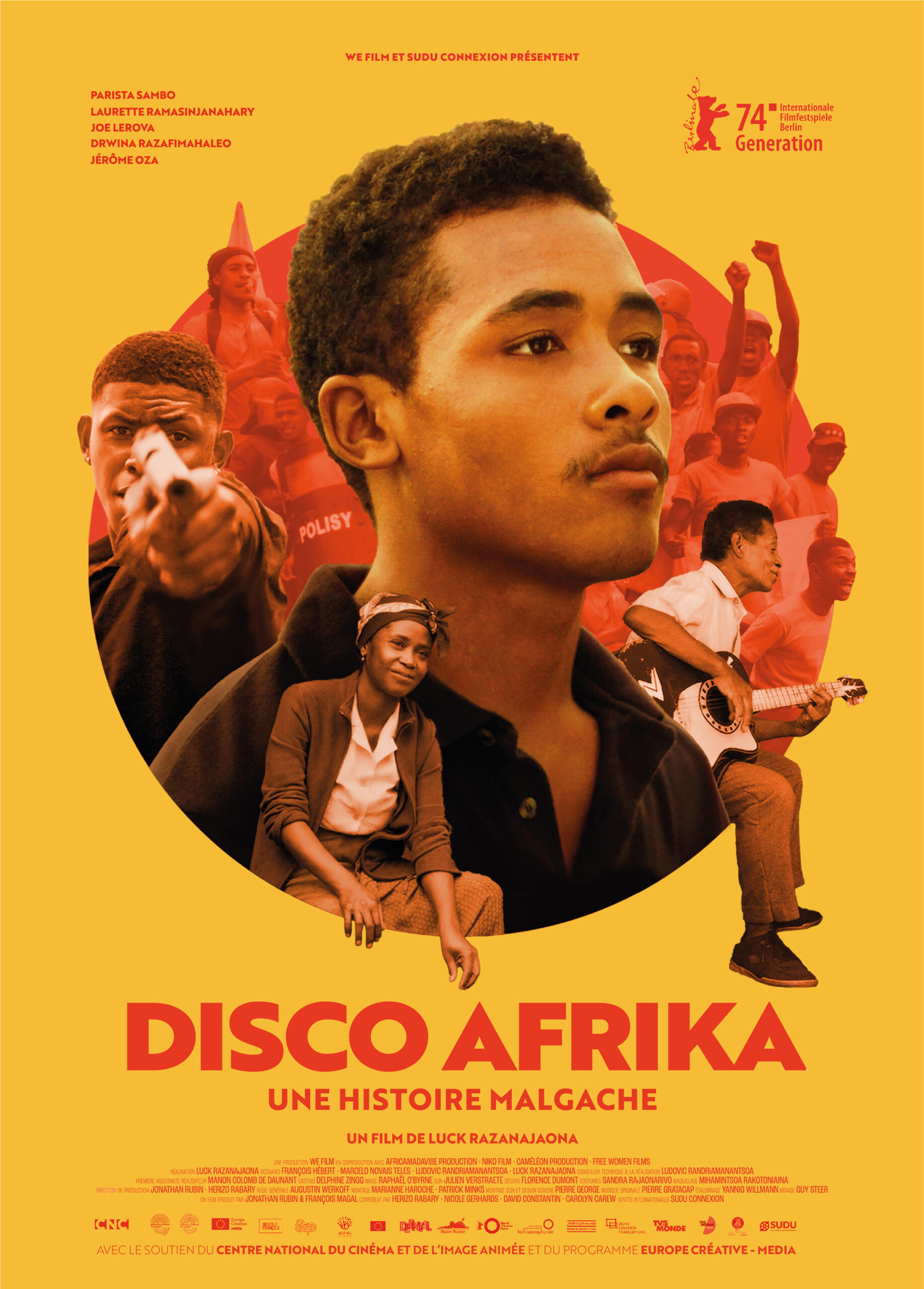

Kwame avoids talking about politics as his father was killed in political protest. But he will soon find out that the one way to move forward is commitment. Review.

Twenty-year-old Kwame is clandestinely chasing sapphires with his friend Rivo when the police protecting the area owned by foreigners killed his friend. All his dream to run the world collapsed. From this moment, an identity quest begins during which he navigates the tough reality of young people in Madagascar. Corruption, poverty and lack of perspectives are among challenges he had to get through.

Disco Afrika questions the state of mind of the young people in Madagascar as they seem not to be interested in political matters. But it raises as well this big dilemma of the desire to bring change and their precarious conditions. In the aftermath of the independence, in 1972, a major political upheaval occurred. This movement had been initiated by students from University and followed by students from colleges. The film evokes a sense of nostalgia of a time when it was about rising up against neo-colonialism no matter the cost.

Music is deeply implicated to question the youth lethargy and the state of watching things going on without doing anything. The director uses “kaiamba”, a music created by artists from Toamasina, an Eastern coast region of Madagascar, to evoke a nostalgia of this time of people’s awakening. Kaiamba playlists of Dédé Fénérive, Ôza Jérôme and Jean Kely & Basth work as powerful prompts to bring audience in the mood of this time when nationalism was the engine to make people move to search for genuine independence.

Disco Africa is also about identity quest as Toamasina is one of the coastal region of Madagascar. “Kaiamba” style was born to challenge ethnocentrism in music in 1970 by bringing new sounds in the Malagasy media landscape and make other regions exist. Luck use this medium that speaks to social and political consciousness to also remind that Madagascar spans across many regions, and the power of the island remains in the diversity of its population.

Subtly, Luck evokes Panafricanism as he’s among of its fervent defenders. His feature debut film aligns among its soundtrack a song from a Garifuna collective, Nibari, a threaten music/culture from Belize. The director explicitly claims this identity even if it’s not quite obvious though his entire filmography. And this is the way to share this struggle of maintaining the African part of us, of our culture alive even if we live apart from the continent.

Luck’s work also explores the interplay of identity and spirituality. When Kwame sees Rivo’s presence recalling him that his Dad’s soul will never find peace if he didn’t lay him to rest in his ancestors’ land, when his friend comes to heal his wound because of doubt, anger and incomprehension, Kwame is offered the opportunity to connect to something greater than himself and then, a sense of belonging. Through these intricate combinations of material and metaphysical worlds, the film is tinged with symbolism and meaning.

The film brings to screen the status quo of the political situation in Madagascar, mainly these cyclical crises. It seems like Malagasy people live the same era over the last 64 years with issues like power outage, corruption and widespread poverty. The film depicts the situation in a timeless way to sound like a call for action. At the end of the journey, Kwame finds his way forward and says “My beloved country, I will stand up to make you proud of me !”

Domoina Ratsara (Film critic based in Antananarivo, Madagascar)