Romania – a small country in the Eastern Europe, but with a history of cinema that overlaps the history of cinema itself. The history of cinema in Romania started before 1900, pushed by film screenings which helped arouse public curiosity towards the new invention and enthusiastic cameramen began making films out of passion for the newly discovered art. Due to rudimentary tehnical conditions, the early films were mainly news, very short (many less than one minute) one-shot scenes capturing moments of everyday life.

The first cinematographic projection in Romania took place on 27 May 1896, less than five months after the first public film exhibition by the Lumiere brothers on 28 December 1895 in Paris. In the Romanian exhibition, a team of Lumiere brothers’ employees screened several films, including the famous L’arrivee d’un train en gare de La Ciotat.

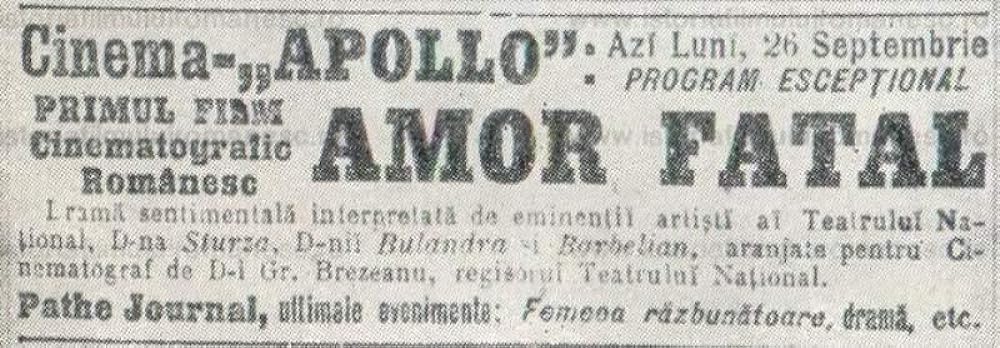

The first Romanian fiction film was Amor Fatal (Fatal Love Affair), starring Lucia Sturdza, Tony Bulandra and Aurel Barbelian, actors from the National Theatre Bucharest. The film was directed by Grigore Brezeanu, a director from the same theatre and the son of the great actor Ion Brezeanu. The film played between 26 and 30 September 1911 at the Apollo Cinema.

During the first two decades of the 1900s the influence of Leon Popescu became crucial for Romanian cinema. He was owner and manager of a cinema, with influential contacts from the country’s financial elite and soon realized the importance and hefty revenue of filmmaking. Under his support were produced films like Independența României (The independence of Romania) in 1912, Amorul unei prințese (The Love Affair of a Princess) (1913), Răzbunarea (Revenge), Urgia cerească (The Sky-borne Disaster), both in 1913, and Cetatea Neamțului (The German’s Citadel) and Spionul (The Spy) in 1914, with all but the penultimate proving to be well below expectations. Popescu, who was in financial trouble after World War I, set fire to his theatre and all his films and committed suicide, it is said.

By the time sound films began to be produced in the western world, the Romanian film industry was enduring a stage of complications. The lack of institutional support, technical facilities, film studios and professional training reduced the quantity of films produced per year; the new feature of sound made it even more complicated. From 1930 to 1939 only 16 movies were produced in the country. To motivate the industry, a 1934 law established a National Cinema Fund with the purpose of creating a material base for Romanian studios and finance productions. Following its creation, the industry started to flourish again with various entrepreneurs developing sound and production companies with modern equipment. Just one year prior, the National Cinematographic Office produced a documentary called Țara Moților (Moților Land), becoming the first film in this genre and eventually winning a prize at the 1938 Venice Film Festival.

After World War II, the influence of communism increased worldwide and communist regimes emerged in most of the countries of Eastern Europe. In Romania, too, the Communist regime came into being with the backing of the USSR. With that, the history of Romanian cinema changed. On November 2nd 1948 meant a new beginning for Romanian cinema. On that day, Decree 303 was signed, regarding “the nationalization of the film industry and the regulation of commerce in cinematic products”.

This can also be called the period of socialist cinema. Following “the teaching of the great Lenin, the ideologue of the social formation of the proletarian class”, who showed that “of all the arts, the most important for us is cinema”, however, not as an art but as an instrument of ideological influence, the newly installed regime fully subsidised the production of films which, as a necessity, as an imperative, disseminated promotion of socialist values.

The filmmakers strived to show the realities of the new society. Socialist films reflected the struggle of the “new man” against the “old retrograde society, a society in which man exploited his fellow man, full of capitalists and men of inherited wealth who sucked the blood of the working classes”. Many films had as their theme the attempts of the retrograde bourgeois-landed gentry class to render futile the new objectives of victorious socialism through their stooges; but these efforts would fail because the Romanian Workers’ (later the Communist) Party, through its activists, would inspire, depending on the situation, workers or peasants toward victory. The same themes were found in documentaries and newsreels. These productions showed “glorious achievements of the working class allied with the working peasantry”.

New studios were built. A new cinema complex was constructed on the outskirts of Bucharest. There were separate studios for fiction movies, documentaries, and cartoons in this complex. At that time, an average of about 30 films were made a year, with the money and facilities available. Despite receiving adequate cash and other facilities, it was accused of censorship and government interference. But it was during this time that many of the great classics of Romanian cinema were released. Romanian films were screened at the Cannes Film Festival, the Berlin Film Festival, and the Moscow Film Festival.

Liviu Ciulei’s Pădurea spânzuraţilor (Forest of the Hanged) (won the Best Director Award at the 1965 Cannes Film Festival), a sombre adaptation of the 1922 novel by Liviu Rebreanu. and Lucian Pintilie’s Reconstituirea (Reenactment) (1968) are considered two of the best Romanian films of all time.

Rebreanu’s novel is seen as a landmark of Romanian modernist literature, being unanimously considered to be the first psychological novel in Romanian literature. Based on true events, the plot follows the moral awakening and the ultimate fall of its flawed hero, a Romanian intellectual who gets caught in a maze of dilemmas about nationality, ethnicity, morality and Christian values. Apostol Bologa is a Transylvanian intellectual who joins the Austro-Hungarian army to impress his childish fiancé. His active role in the hanging of a soldier who had try to desert his regiment triggers his moral and intellectual tribulations after he finds out his reasons. When Bologa’s regiment is later ordered to attack his fellow Romanians, he himself considers the same option. He is wounded though and has a time of relative peace while in recovery, after which he is again confronted with the absurdities of war when Romanian peasants are threatened with hanging after they had been crossing enemy lines to work their fields. This time Bologa refuses to participate in their trial, thus sealing his own fate.

Adapting a novel this introspective is a huge undertaking and Ciulei’s achievement is impressive: he manages to illustrate Bologa’s psychological turmoil with purely cinematic means, most of all a fluid camera movement and impressionistic play of light and shadows, an exquisite and painterly chiaroscuro, and all this without cutting down on the rich dialogues.

Like its literary inspiration, Forest of the Hanged is a powerful plea for humanity, poetic and rough at the same time, and heartbreakingly haunting.

In Lucian Pintilie’s Reconstituirea (Reenactment) (1968) two young romanian students were arrested for a drunken pub fight in which a waiter was injured. Their punishment is to recreate the scene for an educational film warning youths about the perils of alcohol. Overseeing the project is the procurator, who puts on a show of taking the film very seriously, but seems more interested in idling in the nearby stream. Also present are a teacher, who is skeptical about the whole thing, and a policeman, who is quite forceful and enthusiastic about it. An amused girl looks on, her bikini catching the eye of everyone involved. With one interruption after another, and a demand for realism, they struggle to complete the movie.

This politically-charged satire was banned in its home country until after the fall of Communism — is a clever critique of the totalitarian system. The teacher is the conscience of the film, calling into question the effectiveness of the government’s methods. The efforts to make this film of dubious usefulness are plagued by chaos, incompetence, uncertainty and apathy. The cacophony of the soundtrack — a malfunctioning car horn, a woman screaming about a car that’s killed one of her squawking geese, an ambulance siren, the loud whirr of the camera — adds a layer of confusion and unease, unwelcome audio intruders at this placid location. The end result of the government’s “solution” to the problem is, of course, more damaging than the original crime.

The film is said to be one of Romania’s best, and an inspiration for the “Romanian New Wave” of the 21st century.

The end of communism also changed filmmaking in the country and set the grounds for a new era. Now, directors exercised creative liberty without worrying about persecution or censorship.

At the beginning of the 1990s, the industry tried to capture the attention of capital investors, with very little results. Although the film was freed from severe censorship, early filmmakers faced a crisis during which they could not find the necessary financial resources. Lack of money hampered their filmmaking. Filmmakers examined the Communist period and the economic and spiritual crisis in the country. Production often depended on the state grants, awarded by a jury; it was found that many of the grants were awarded within a clique of earlier members of the jury, twisting the goal of the system.

Lucian Pintilie’s film Balanța (The Oak) was screened at the 1992 Cannes Film Festival. This film, a French-Romanian co-production, is Mr. Pintilie’s reaction to the 1989 collapse of the Communist regime in his country and his expectations for the future. It begins as a nightmare and ends with a vague expectation of the break of day.

Among other things, “The Oak” is about a young schoolteacher, after the death of her father, a former big shot in the secret police, though you wouldn’t know that he had ever been powerful from the opening scenes. She accepts a job outside Bucharest, is gang-raped en route to the assignment, learns that her father was something less than a hero and meets a man who is, in his way, just as off the wall as she is. He is a cheerfully sardonic doctor whose relations with the regime are not good. He refuses to follow protocol and insists on taking care of a patient whom the regime would like to see die.

Though her is a spiritual journey, Mr. Pintilie dramatizes it in the bitter ways of social satire. The movie has the tempo of cabaret theater. It is wildly grotesque, shocking and sometimes very funny. The details are vivid. The authorities are alternately fearful, blundering and good-hearted. Late in the film, as the characters reach some kind of understanding, Mr. Pintilie seems to suggest that there is still hope for Romania, though it’s not just around the corner.

A decade later, in the early 2000s a group of young people came up with a low-cost film-making method. They have come up with a new concept called Minimal Cinema and presented the world with low cost and at the same time completely different films. They astonished the world by creating a new paradigm in content and storytelling. It took the international success of filmmakers disliked by the juries to change the system. Two Romanian directors competed in the Directors’ Fortnight section parallel to the Cannes Film Festival with Cristi Puiu’s first feature film Marfa si banii (Stuff and Dough) (2001) and Cristian Mungiu’s Occident (2002). This became the new movement known as the Romanian New Wave, followed by Moartea domnului Lăzărescu (The Death of Mr. Lăzărescu), also directed by Cristi Puiu, in 2005. This new era is marked by realistic stories showcasing the transition from communism to a free-market economy, the struggle of the youth to find jobs, and the corruption found in the new capitalist system.

For the past two decades, world cinema has been mostly discussing Romanian cinema. Romanian films are exhibited at film festivals around the world and became their attractions. Through these films, Romania has introduced a new movement to the world known as the Romanian New Wave, which found its place in world cinema.

The Romanian New Wave presents to the world the concerns and anxieties of modern Romania. At the same time, it criticizes the hypocrisy that exists in society. The film “Babardeală cu bucluc sau porno balamuc” (Bad Luck Banging or Loony Porn) (2021), which won the Golden Bear Award at the 2021 Berlin Film Festival, is one of the best films to expose such hypocrisy in Romanian society. This film by Radu Jude reveals not only the attitude of the modern Romanian people towards sexuality but also its relentlessness. It also looks into question the duplicity of Romanian society towards various issues. It exposes the anti-people attitudes of the church and the military towards the people’s struggles from time to time.

The era marked by the world as the Romanian New Wave begins with Radu Mihăileanu’s ‘Train of Life’. The film won the FIPRESCI Award at the Venice Film Festival.

The first tendency to appear with the fall of the communist regime was the Romanian people’s desire to migrate western “paradise” from the country. People began to compete to migrate to the western capitalist countries. Parents began forcing their daughters to marry men from other European countries. Early Romanian cinema reflected the intensity of this desire. Europe was the paradise of their dreams. “Occident” is a bitter comedy that focuses on the western migration of Eastern European youth. This satirical comedy film by Cristian Mungiu depicts the Western immigration efforts of Romanian youth. And so is the future of those who fail. The film follows the style of the famous film Rashomon style of Kurosawa through the visuals of different people walking through different places and meeting, parting, and meeting again. Unemployment and poverty in post-Romanian society is the main theme of this movie. Even love and marriage were to be abandoned for money and employment in this film. The protagonist ‘Luci’ of this film has to abandon his girlfriend who wishes to marry a western husband, and Mihaela, who is forced to marry a foreigner, is both a sign of poverty and unemployment.

But Cristi Puiu is considered to be the mastermind of Romanian New Wave cinema. His film “The Death of Mr. Lazarescu” shocked the film world. Later, Cătălin Mitulescu’s film, ‘The Way I Spent the End of the World’, won an award at the Cannes Film Festival, and Romanian cinema became the new face of world cinema. Since then, several young directors have appeared in various festivals, creating a series of excellent films.

Cristian Mungiu, Cristi Puiu, Cristian Nemescu, Radu Muntean, Corneliu Porumboiu, and many young directors, including Radu Jude, have emerged as spokespersons for the Romanian new wave. Those who rewrote the history of Romanian cinema were spent their childhood and youth during the communist era. They have traversed the difficult path from communism to capitalism. Who are aware of the differences and nuances of the two systems. This experience is evident in their films.

Anyone who approaches Romanian new wave cinema can see a film that is struggling to break free from the influence of communism. The words of the famous Romanian director Lucian Pintilie – that communism has disappeared as a state but continues as a state of mind – are relevant here. New filmmakers still do not reject communism in their films. In addition, films such as Radu Jude’s “I do not care if we go down in history as barbarians” are a sharp critique of anti-communist persecution stories. The story is about the political interventions of a playwright trying to recreate the Jewish Holocaust of the pre-communist regime. In the film, Jude deals with the natural inhumanity of governments. In doing so, he reinforces the Marxist notion that the state is an instrument of repression. Most of the films still have not strayed from the sphere of influence of communism. Moreover, they do not question the merits of communism. Most of the films deal with the practical failures of communism. Moreover, these films ruthlessly attack the bureaucratic hegemony and nepotism that has grown up in the state. Beyond that, these films show great concern about the future of the country in the new capitalist market system.

Although the regime shifted from communism to capitalism, it generated a different reaction from the general population. The people approached the new system with suspicion and apprehension. One of their main doubts was that capitalism did not have the security given by communist rule. Cristi Puiu’s ‘Sieranevada’ is a film that discusses such concerns in post-communist society. The subject of their discussion was the uneasiness about the future through a conversation between family members who attended their father’s death anniversary. In the film, we see a society that is concerned about the future of post-communist Romania and the growing influence of religion in the new society. Anxiety about the future is reflected in their conversations. We can also consider the death anniversary of the father as the “death anniversary” of the Romanian Communist regime. The film should then be approached as the anguish of a society that has lost its head. We can see the pastor as the epitome of a religion migrating to the gap created by communist rule.

Cristian Mungiu’s ‘Beyond the Hills’ is a film that exposes the growing influence of religion as a threat to post-communist society. The film points out that religion is beginning to grow to a point where it affects all spheres of life and determines life itself. In the film, Mungiu travels through the dark paths of faith and religious fanaticism. The heart of the movie is the reunion of two friends who grew up in an orphanage. By then a friend had joined the monastery to become a nun. The director reinforces the influence of religion in the new Romania through the heroine’s attempt to extradite her from there and immigrate to Germany with her. The heroine’s problems are further complicated when her friend decides to remain as a nun and the church intervenes in the matter. Church officials imprisoned the friend who has been violently abusive and subjected to antiquated treatment. Mungiu presents a glimpse into the intense religiosity and primitive witchcraft that Romanian society is going through. The last shot makes it clear that it is utterly dark and hopeless. In the last shot, Mungiu says that even the exact interventions of the legal system are being covered up by the ferocious mud of religion.

Another important subject in the Romanian New Wave is the breakdown of family ties. Many films reflect the breakdown of the established family relationship. In these films, we see the political breakdown spreading to family relationships. These disturbances in family relationships are the result of the indiscipline that emerges in a society that has suddenly moved from strict discipline to “independence.” The main theme of many films is how disgruntled partners part ways with each other and the discomfort it causes in family relationships. Family heads who fall in love and have sex with another woman while living with their wives in Mungiu’s Graduation and Radu Muntean’s Tuesday After Christmas If the hero of graduation is prevented from divorcing his wife by his intimacy with his daughter, then the protagonist of “Tuesday after Christmas” has no problem at all. The love of the protagonist of Graduation towards his daughter eventually leads him to jail. His crime was that he tried to manipulate her exam marks by artificial means to secure her future. It’s caught and he’s arrested. He is still trying to save his own family, even though he is reluctant to leave his girlfriend. But the hero of “Tuesday After Christmas” has none of these worries at all. The heroine of “I Do Not Care If We Go Down in History as Barbarians” is pregnant with a father of two. The girlfriend’s pregnancy annoys him. He is trying to get an abortion to secure his own life. His girlfriend’s life is not a matter of concern for him. All these films deal with the changing Romanian concept of family. Moreover, the fact that women are the main victims of these changes is evident in all these films. All this indicates that Romanian society is becoming more anti-feminist.

Despite these inconveniences in family relationships, the relationship between parents and children and sibling relationships tends to be stronger in these new films. Cãlin Peter Netzer’s “Child Pose” and Florin Șerban’s “If I Want to Whistle I Whistle” deal with such an issue. Child Pose describes the plight of a mother who tries desperately to save her son who was involved in the murder of a young man in a car accident whereas “If I Want to Whistle I Whistle” is about the relationship between a convicted felon and his brother. The brother fights with his mother who abandoned them, for his brother and he goes back to jail.

Christian Mungiu’s “4 Months, 3 Weeks, 2 Days” is about personal freedom. During the reign of Nicolae Ceaușescu, abortion was banned by decree of 1966. The truth is that it is women who suffer the most. Their freedom of choice is denied. But there were so many illegal agents operating abortion centers shows the weakness of this law. The film depicts the experience of a girl and her friend who set out to have an illegal abortion. The film is about the hardships and persecutions they face while traveling outside the law. Beyond that, the film focuses on government encroachment on the privacy of individuals. Moreover, the film gives us a picture of the corruption and crime that existed at that time. The film tells the story of how the government’s restrictions on individual freedom can stimulate the criminalization of society.

Corruption and nepotism are a social menace in any society. And these new wave directors present such subjects as satires in their films. One such great film is “Tales from the Golden age”. The film has six episodes that showcase the old regime’s subjugation and corruption. The film is a great satire and each part is directed by different directors. Every piece of it just happens in capitalist societies also. But the director seems to mean that this should not be under communist rule. The first part is about the arrangements to be made in connection with the visit of the Party Secretary. It eloquently describes the exercise of power by the “pilot” troupe that came to observe it and the anxieties of the local government. The second part deals with the humorous but serious problem of the incident where the newspaper itself had to be stopped for a day due to a flaw in the photo publishing because of the hat of the president. The film is a sharp critique of the Romanian Communist regime, but only of a critique of any regime. The six-part film deals with corruption, nepotism, and individual attempts to please the leadership. The film deals with the efforts of individuals to overcome government restrictions on individual freedom and the social problems it creates. At the same time, it deals with the crime situation that is plaguing unemployed youth. A young man and woman who were unemployed visited apartments and lie and collect empty bottles to sell them for a living. They are eventually caught by the police. This points to the employment problem facing Romania.

“12:08 East of Bucharest” is a satirical film about a drunken professor who tries to take over the credit of the 1989 anti-communist revolution. Audiences question the professor’s claim that he was at the forefront of the revolution during a talk show on the anniversary of the revolution. Thus, the veracity of his claims is being questioned. Director Corneliu Porumboiu questions the claims made by those who played no part in the revolution. It eventually points out that any revolution is carried out by common man and not by intellectuals.

Revolutions have always been the womb of art. Iranian cinema is the Iranian revolution. The strength of the art of Latin Americans is the Latin American riots. German cinema rose from the debris of fascism. Those who have given birth to great works of art around the world are those who have swum the rivers of persecution before. Revolutions may have failed, but their impact on art is always positive. Romanian cinema is the product of the suffering. The people of Romania are not recovered from the wound created by communism and oppression. Its an open wound that will bea healed, including by cinema.