The key question of Hong Kong horror in recent years is: ‘Are there any ghosts in this ghost film?’ This question has become frequently asked by audiences as many contemporary Hong Kong horror films render the spectral experience as a result of a dream or hallucination.

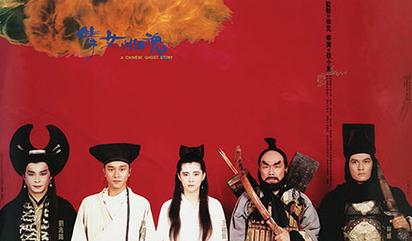

Thanks to the Mainland and Hong Kong Closer Economic Partnership Arrangement (CEPA), which has attracted many Hong Kong filmmakers to go for a huge market in Mainland China, they have to fit their creativity inside the box of ‘co-production’ confined by the national film regulations. In particular, supernatural subjects are discouraged because they are labelled as promoting superstitions. This condition has become a challenge to the Hong Kong industry used to produce numerous horror films in its golden era, such as Mr. Vampire (1985) and A Chinese Ghost Story (1987). While the number of horror films plummeted with Hong Kong production in general in the past 20 years, those filmmakers who still make ghost movies take two strategies. First, they make ‘ghost films without ghosts’—what appears as evil spirits in the film will be explained as the results of the characters’ dreams or psychological issues. The second way is to risk (if not give up) the profitable market in Mainland China to keep the ‘Hong Kong spirit.’ Some films even make ‘We do have ghosts!’ as a selling point, suggesting a local authenticity of ‘Hong Kong style’ horror. I am going to review how this undead genre has kept hopping and haunting since CEPA’s implementation.

Defining a genre is always difficult. I manually count ‘Hong Kong horror’ from 2004 to 2023 and try to be inclusive, including co-productions, horror-comedies, and some thrillers without ghosts. There are less than 90 films in this period, less than 5 per year on average. The general trend slides down, unsurprisingly, starting from the peak in 2004. However, we observe two slight bumps worth exploring: around 2013–15 and 2021–23.

Hong Kong horror indeed has benefited from co-productions—with Southeast Asia, though.

Before 2010, Applause Pictures, founded by filmmaker Peter Chan Ho-Sun and partners, envisioned a ‘pan-Asian’ market, co-producing films with Korea, Japan, and Thailand, notably the Three series. Moreover, Applause nurtured the new generation of horror auteurs, the Pang Brothers (Danny Pang Phat and Oxide Pang Chun). Since the success of The Eye (2002), starring Angelica Lee Sinje from Malaysia, the Pang Brothers made more ghost movies in the 2000s, often situated in Thailand, incorporating the aesthetics of contemporary Japanese horror (J-horror). Besides playing with jump scares in a spectral atmosphere, the Pang Brothers also introduced advanced technology in this period, such as the CGI hell in Re-cycle (2006) and the 3-D Child’s Eye (2010), indicating Pang Brothers’s contribution to quality horror films targeting a transnational market.

Hong Kong cinema has always thrived on cross-border capital, talents, and markets. Although Applause and Pang Brothers’ initiatives could not save Hong Kong horror from dropping to the trough at the beginning of the 2010s, Southeast Asian co-productions remain essential to this genre. For example, Malaysian company Asia Tropical Films has contributed to Hungry Ghost Ritual (2014), directed and starring Nick Cheung Ka-Fai, and The Sleep Curse (2017), directed by Herman Yau Lai-To and starring Anthony Wong Chau-Sang. MM2 Entertainment from Singapore has set up its branch in Hong Kong and produced Ghost Net (2017), Buyer Beware (2018), and Walk With Me (2019), featuring a new generation of Hong Kong performers. Notably, Back Home (2023), the directorial debut of Nate Tse Ka-Ki, blends social allegory and local folk horror in a tongue-cutting traumatic story, echoing the recent changes in Hong Kong’s social milieu. This film also features the legendary Bai Ling, who delivered a stunning performance in Fruit Chan’s cannibalistic horror Dumplings (2004).

The bumps around 2013–15 may be explained by the surge of local activism and ethos resulting from the existential crisis of Hong Kong cinema, and the industry put more effort into incubating a new generation of performers and filmmakers. The horror genre provides opportunities for more local, small-budget projects with emerging stars and directors, as well as job opportunities for the industry in general. Similar cases are found in the crisis caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, in response to which some film companies invested in thriller-horror films to keep the industry alive. For example, Media Asia Film produced a series of three Tales from the Occult films from 2022 to 2023, each film an anthology of three short stories. This practice is not new, as exemplified by 01:00 A.M. (1995) and Midnight Zone (1997), directed by Wilson Yip Wai-Shun. Earlier examples of horror anthologies are two films of the Tales from the Dark series in 2013, adapted from novels by Lilian Lee Pik-Wah. One should note that these films not only give opportunities to younger directors but also seasoned ones like Fruit Chan and Li Chi-Ngai.

A few observations of Hong Kong horror films in these two decades are noteworthy: opportunities for new talents to hone their skills, ‘ghost’ films still prevailed, and horror as the social commentary.

Low-budget horror films provide a stage for emerging performers on screens. In the 2000s, popular duo idols Twins took leading roles in The Twins Effect and The Death Curse in 2003. Among them, Gillian Chung Yan-Tung headed the bill in 49 Days (2006) and Naraka 19 (2007). While Stephy Tang Lai-Yang, endorsed by the Hong Kong audience today, starred in Dating Death (2004) and In Love with the Dead (2007). In the 2010s, we saw Chrissie Chau Sau-Na, who began her career as a gravure model, starring in Womb Ghosts (2010), Vampire Warriors (2010), and Hong Kong Ghost Stories (2011). A more recent example is Carlos Chan Ka-Lok, as the main cast of Buyer Beware (2018), Binding Souls (2019), and Ghost Wedding (2022). While the 12-member boy group Mirror has become a superhit name in recent years, two members, Anson Kong Ip-Sang and Anson Lo Hong-Ting, appeared as the spotlight of Back Home and It Remains, respectively, in 2023. Nevertheless, to what extent these horror films contribute to the young stars’ reputation and acting craft is doubted, as many of these films are far from successful at the box office and critical reception.

Low ratings of these ‘young horror’ films may be explained by the unskilled performance of young idols who lack professional training in acting or sloppy plots in ‘ghost films without ghosts’ (such as Carlos Chan’s ‘dream closure’ in Buyer Beware and ‘inherited traumatic hallucination’ in Ghost Wedding). It is also unhelpful that these films casting young stars are not really youth-centred in terms of the narrative’s perspective. Young people in these horror films often appear reckless, irresponsible and weak-willed, making themselves subject to evil power as a punishment. Moral teachings in horror stories are not new in Asian culture, but the young voices are often marginalised. In Pang Brothers’ The Eye 10 (2005), a group of young people played with ten ways to see ghosts with tragic results. In Hide and Seek, one of three short stories of Tales from the Dark 2, an alumni group returned to their alma mater before its closure, ignoring the watchman’s warning, and played a forbidden game with total loss. Some Hong Kong horrors are inspired by contemporary life that is inseparable from technology. Social Distancing (2022), directed by Gilitte Leung Pik-Chi, shows how a traffic-craving YouTuber gets entrapped in a virtual haunted network and exhorts young people not to be addicted to the web and that they should care about their families. These films’ conservative approach reveals an ambiguous attitude towards the past of Hong Kong horror.

Demonic beings often indicate our anxiety about what should be past but have not passed, haunting us with uncanny returns. ‘The reincarnation theme is the backbone in all ghost stories, and it is the ghost story which defines Hong Kong’s horror genre,’ says Stephen Teo, who highlights the hybridity in Hong Kong culture as seen in horror films. Its ontological conflicts between Western capitalism and Chinese socialism, and between premodern traditions and modern life, are often negotiated in horror films through the motif of uncanny return, represented by vampires, ghosts, or other demonic beings. Hong Kong horror in the past two decades concentrated on ghost stories (including those that expel the spirits with a psychological approach), unlike many genre-crossing films in the 1980s where horror was often blended with fantasy, comedy and wuxia, such as Mr. Vampire and A Chinese Ghost Story.

Hong Kong-style vampires still occasionally hopped on the screen, featuring battles between Taoist vampire hunters and vampires, as well as human-vampire romance. In the local context, one should not mistake Twilight (2008) as the inspiration for such alleged necrophiliac romance—exemplified in Vampire Cleanup Department (2017) by the kiss of the hero (the hunter) that revitalises the stiff of the heroine (vampire) and turns her a cute sweetheart (played by Lin Min-Chen from Malaysia). The vampire romance on the Hong Kong screen may date back to the TV drama trilogy My Date with a Vampire (1998, 2000, 2004) produced by Asia Television. Dating a Vampire (2006) is another example, whose plot is deemed by many audiences as copying A Chinese Ghost Story. Notably, Rigor Mortis (2013), directed by Juno Mak and starring the vampire film icons Chin Siu-Ho and Anthony Chan Yau, keeps a distance from the comedic-fantasy style but incorporates J-horror aesthetics for an eerie ambience, making it a new classic among the fans of Hong Kong horror.

Esther Cheung suggests the idea of ‘spectral criticism’ as an analytical framework for the urban space represented in Hong Kong cinema beyond particular genres. This approach allows us ‘to see connections and analogies between inconceivable and disconnected events and moments’ in interstices where the past/absent and the present overlap, enabling an empathetic mode of seeing as: ‘I see you are not there.’ The spectral analysis helps us see the marginalised beings’ disappearance and ghostly reappearance in the city. A number of Hong Kong horror films function as social commentaries on urban development, inequalities, and the cramped and cluttered homes of the lower class. In Home Sweet Home (2005), directed by Soi Cheang Pou-Soi, the ‘monster’ (Karena Lam Kar-Yan) hides in the shadows in a luxury condominium, appearing as a threat to middle-class families living there. The ‘monster’ is indeed a victim of urban redevelopment, whose original home was located where the high-end condo stands after the former local community was demolished.

Dream Home (2010), directed by Edmund Pang Ho-Cheung, plays with the cult aesthetics reminiscent of the ‘Category III’ exploitative films in the 1990s. It is a slasher film inspired by the skyscraping house prices in Hong Kong, providing an excuse to the heroine who tries to slash the price along with the residents’ bodies in an expensive apartment building. Fruit Chan’s Coffin Homes (2021) shares a similar cult aesthetic in an ironic manner, producing a ridiculous dark sense of humour for the absurd conditions of Hong Kong’s real estate market. The hero is a real estate agent forced by a murderous ghost to sell the latter’s flat, and the hero’s father is a landlord profiteering on tiny subdivided units, only troubled by a mischievous boy’s ghost. Similar horror stories are seen in anthology films such as Stolen Goods in Tales from the Dark 1, directed and starring Simon Yam Tat-Wah, and Crowd You Out in Ghost Net (2017), directed by Wong Kwok-Keung. These films reveal what is more horrible than demons—the structural evil of greed in the name of development.