Menstruation has always been underrepresented in Malayalam cinema. This could be for a variety of reasons. Firstly, menstruation is a tabooed topic, laden with several cultural proscriptions and corresponding linguistic interdictions, even in modern Kerala. Secondly, in Kerala, just as in the case of contemporary patriarchal cultures all over the world, the most desirable female body is a ‘civilised body’ that is ‘closed-off from the outside world and dry’ (Lupton, 1998, p. 86) and not threatened by fluids that would ‘seep or ooze and thus challenge control’ (ibid.). Therefore, for the ‘panoptical male connoisseur’ (Bartky, 1995, p. 247), an ideal female body should ‘appear’ as ‘not-menstruating’, which is evident in most of the Malayalam sanitary pad commercials that encourage women to conceal the visual and olfactory markers of menstruation. Moreover, in those occasional instances when menstruation indeed becomes a part of a movie script, its representations are often from the point of view of the ‘male’, regularly undermining the female experiences of menstruation. In this paper, I examine a handful of Malayalam feature films, both mainstream and parallel, produced between 1971 and 2020, in order to draw out the chief representational themes of menstruation exemplified in them. And, through a feminist perspective, I look at how these themes manifest the gendered power relations in the society.

Menstruation as catastrophe

The feature Pavithram (T.K. Rajeev Kumar, 1994), tells the story of a young girl by the name Meenakshi whose mother dies in childbirth. She is brought up by her elder brother whom she addresses as Chettachan – a term coined by combining chettan (elder brother) and achan (father). The first half of the movie shows her life as an innocent village girl who is oblivious to the ways of the world. However, the arrival of menarche turns out to be disastrous to her otherwise serene life. This is symbolically captured by the flowing, broken pieces of mirror in a stream on the banks of which she menstruates for the first time. It is unfolded in the movie thatafter thirandukuli, the traditional menarche ritual; Meenakshi’s personality undergoes a drastic change. She grows aloof from her brother and others who are close to her. Soon, she moves to the city for higher education, becomes ‘modern’, develops the habit of heavy drinking, and hangs out with an obstreperous bunch of friends. All of this brings tragedy to her life and this takes a toll on Chettachan’s mental health. Similarly, Lal Jose’s Nee-Na(2015)presents a flashback from the female protagonist’s teenage years, where her father puts an end to her tomboyish ways once she reaches menarche. She is constrained from meeting her male friends and several restrictions are put on her mobility and behaviour. This makes her detest menstruation and call it ‘the bloody red signal’. Soon after, she takes to drink and smoke and even grows apart from her parents. This brings grief to her whole family. Another Malayalam family drama Mummy & Me (Jeethu Joseph, 2010) presents a soundtrack tracing a girl’s growth from infancy to adolescence. While she is shown as being dependent on and obedient to her mother during her childhood years, the arrival of menstruation instigates unfavourable changes in her behaviour. Shortly, she begins to fill the walls of her room with sensuous pictures of male celebrities, takes an interest in romantic novels, refutes any kind of help from her mother in daily life, initiates an unconventional relationship with a virtual friend and picks up frequent fights with her mother – eventually disrupting the peace of the family unit. Nevertheless, in all of these movies, the problematic menarcheal girls, in due course, ‘learn from their mistakes ‘and allow themselves to be disciplined by her parents, religious authorities, or modern psychiatric treatment. They adopt the behaviours, attires and attitudes that the patriarchal society deem fit for a ‘proper woman’. Here, a few things become apparent. Firstly, in these coming of age movies, menstruation is set forth as a harbinger or a precondition to the female protagonists’ acts of misconduct, delinquency and unruliness. Consequently, they are discerned as harbouring a certain kind of ‘potentially malevolent’ power that can launch an array of catastrophes on themselves, their families and the society. This could be because, during menarche, a young girl is perceived as a ‘liminal’ entity – in the margins of juvenility and adulthood, dangling in the middle and slipping through binaries. She is ‘the in-between, the ambiguous, the composite’ (Kristeva, 1982, p. 04).And, ‘to have been in the margins is to have been in contact with danger, to have been at a source of power’ (Douglas, 1966, p. 98). However, her power is eventually contained and sequestered by the patriarchal order by fitting her into the conventional moulds of womanhood.

Furthermore, female bodies are demonstrated not only as spawning dangers and catastrophes, but also as inviting them, ‘eminently at the time of menarche, the first menstrual period’ (Bobel, 2010, p. 31). For instance, even in movies that are hailed to occupy an artistic high ground, menarche is rendered as bearing dangerous and disastrous consequences for the menarcheal girl’s life and well-being. Adoor Gopalakrishnan’s critically acclaimed Nizhalkuthu(2002) narrates the death of Mallika,a 13-year-old girl. Soon after her menarche celebrations, she becomes an object of her brother-in-law’s sexual desire and is eventually raped and murdered by him. Similarly, in Bhoothakkannadi (Lohithadas, 1997), a young menarcheal girl Meenu – a figment of the male protagonist’s imagination – suffers the same fate, albeit in an imaginary world, reinforcing the catastrophic ramifications of menarche.

Menstruation as sexual readiness

In Kerala, menarche called for an elaborate rite by the name thirandukalyanam among various Hindu castes, up until the second half of the 20th century. However, there was a significant diminution in these celebrations in modern Kerala, owing to various social, cultural, economic and historical changes such as the community reformism movements, missionary activities, increased participation of women in the public sphere, and the precipitation of a new menstrual discourse by modern medicine and the media. Nevertheless, Malayalam movies have been instrumental in the surreptitious preservation, repetition and reproduction the conventional sentiments and values surrounding thirandukalyanam.For instance, movies such as Karakanakadal (K.S. Sethumadhavan, 1971), Thulavarsham (N. Sankaran Nair, 1976), and Pavithramshow detailed illustrations of thethirandukalyanam rituals, with connotative songs in the background. Most of these songs proffer lyricsthat equate theevent of menstruation with ‘flowering’ and the menstruating girl with ‘a red flower’ (thechippoo), ‘a seasonal flower’ (rtumatippoo), or ‘a blooming flower’ (virinjapoo) implying that with menstruation, a girl’s womb is in readiness to bear fruits/children. Such examples are easily multiplied in many other movie songs such as Vasumati rtumati from Gandharvakshetram (A. Vincent, 1972), Thechi poothe from Bhrashtu (Thripayar Sukumaran, 1978) and Poovamkuzhali from Vadakakk Oru Hridayam (I.V. Sasi, 1978). Likewise, several movies employ visual imageries to render a menstruating girl and a flower as analogous. In the coming of age film Rathinirvedam (Bharatan, 1978), the teenaged Shanti menstruates for the first time while riding a bicycle. It is indicated that she notices blood on the cycle saddle and realizes that her first period has arrived. However, the viewers are presented with a collage of swaying flowers, signifying her menstruation. In all of these instances, the ‘flower’ analogy clearly signifies the sexual readiness of menarcheal girls – they are nothing but flowers and wombs to be pollinated and inseminated by men. Similarly, in a number of movies (see, for instance, Bhoothakkannadi,1997), a girl’s menarche is implied by euphemisms such as vayassariyichu (she is of age), valiya pennayi (she has become a big girl) and theraluka (she has become brimful), indicating that her body is ready to receive a man. This is also reminiscent of the fact that in old Kerala, especially among the Nayar community, thriundukalyanam was a ritual intended to attract upper caste men to enter into sambandham with Nair women(N.K. Jose, 2018, p. 22) and consequently, the expressions such as vayassariyichu (she is of age) served as reminders of her availability for sexual unions. Moreover, by portraying women as passive receptors of male sexual activity and semen, these songs and euphemisms endorse the ‘penetrative’, ‘impregnating’ and ‘active’ aspects of male sexuality, albeit indirectly, while tying women strictly to their sexually receptive and reproductive roles.

Menstruation as joke

In any joke that is connected to the biological processes of women, it is the female ‘imperfect body’ that gets highlighted (Bemiller & Schneider, 2010, p. 476). Thus, by depicting menstruation as something that can elicit shame, embarrassment and laughter, movies aid the production and sustenance of a ‘sexist culture’ (Laws, 1990, p. 29) and a patriarchal ideology that renders male bodies as normal and healthy and women’s bodies as anomalous and comical. For instance, in the movie Neelakurukkan (Shaji Kailas, 1992), a facetious college student Binoy tries to woo a sharp-tongued Meera, who rejects his advances. However, during their brief encounter in front of a convenience store, Meera gets embarrassed and is briefly silenced as her shopping bag falls off, revealing a huge pack of sanitary pads. However, the sight of the packet causes Binoy as well as an onlooker – Fr. Illikkoodan, to laugh. Similarly, a scene from the Malayalam movie Chocolate(Shafi, 2007), happens to be an excellent example of constructing menstruation as the ‘ladies’ problem’ in jokes. Such jokes also often depict common cultural notions about a certain ‘male innocence’ (Newton, 2016) when it comes to understanding menstruation. The movie tells the plight of Shyam, who happens to obtain the only one seat reserved for men, in a women’s college. There is a classroom scene where the girls pass on a small package, covered by a piece of newspaper, from one end of the classroom to the other. When the package reaches Shyam, the lecturer, who is also a woman, spots it and asks him what it is. He squeezes the packet with his fingers and answers that it might be bread. Finally, he opens it and finds out that it is a packet of sanitary pads and gets uneasy. He glances at the packet quite a few times and tries to laugh off the situation. This erupts laughter among the girls. Eventually, the lecturer suggests that some girl take it from him. Here, a man holding a packet of sanitary pads becomes a laughable image for it is founded on a patriarchal ‘us versus them’ mentality, juxtaposing women as the ‘other’ in comparison to men who are perceived as ‘normal’(Bemiller & Schneider, 2010, p. 468). That is, the ‘other’ and its ‘abnormal’ biological processes are perceived as nothing but anomalies to be made fun of.

Menstruation as an instance of female bonding

Caring for a girl at menarche in pre-modern Kerala required a range of work to be done by her female kin and most of this work demanded a detailed knowledge of and associated skills regarding the cooking of ceremonial food items, creating a dietary plan to meet the nutritional needs of the girl, erecting marappuraand giving her obligatory ceremonial baths, preparing special concoctions to fight dysmenorrhea and cramps and beautifying the girl with customary face masks and body packs. Also, in most cases, women of the menarcheal girl’s caste performed a variety of ritualistic dances and ululation, facilitating the establishment of her womanhood culturally. These aspects are reflected in the thirandukalyanam scenes of several movies as late as in the 1970s. For instance, Thulavarsham(1976)features an elaborate Kummi dance performance by a group of women at the teenaged Ammini’s thirandukalyanam rituals. The ritual is shot as an all-women event where they sing lyrics that contain sexual double-entendres and twirl and sway with unrestricted body movements. However, this menstrual bonding between women, mostly mediated by caste and customary practices, developed into a type of ‘inclusive bonding’ towards the end of the 20th century. That is, owing to the social, historical and demographic changes, menstrual bonding is now extended to and sometimes even shifted to women outside one’s family and caste such as friends, roommates, colleagues and so on. For example, in Shalini ente koottukari (Mohan, 1980), best friends Ammu and Shalini fondly reminiscence about the first time Shalini shared the particulars of her first menstruation with Ammu. Similarly, in Notebook (Roshan Andrews, 2006), when Sreedevi, a 11th grade student is shown as getting her periods unexpectedly, her protective friends Sarah and Pooja come to her assistance. Therefore, Malayalam movies, albeit only a few, expounds that there is a certain form of bonding and intimacy between women, centring on the practices of menstruation and menstrual care, which extends the ‘possibility of plural paths to intimacy’ (Simon, 1987, p. 110) in the lives of women. Nevertheless, constituting menstruation as an instance of female bonding also manifests the patriarchal perspective that menstruation is essentially a ‘woman’s problem’ – one that should be discussed and dealt with, only by women.

Shifting representations of menstruation

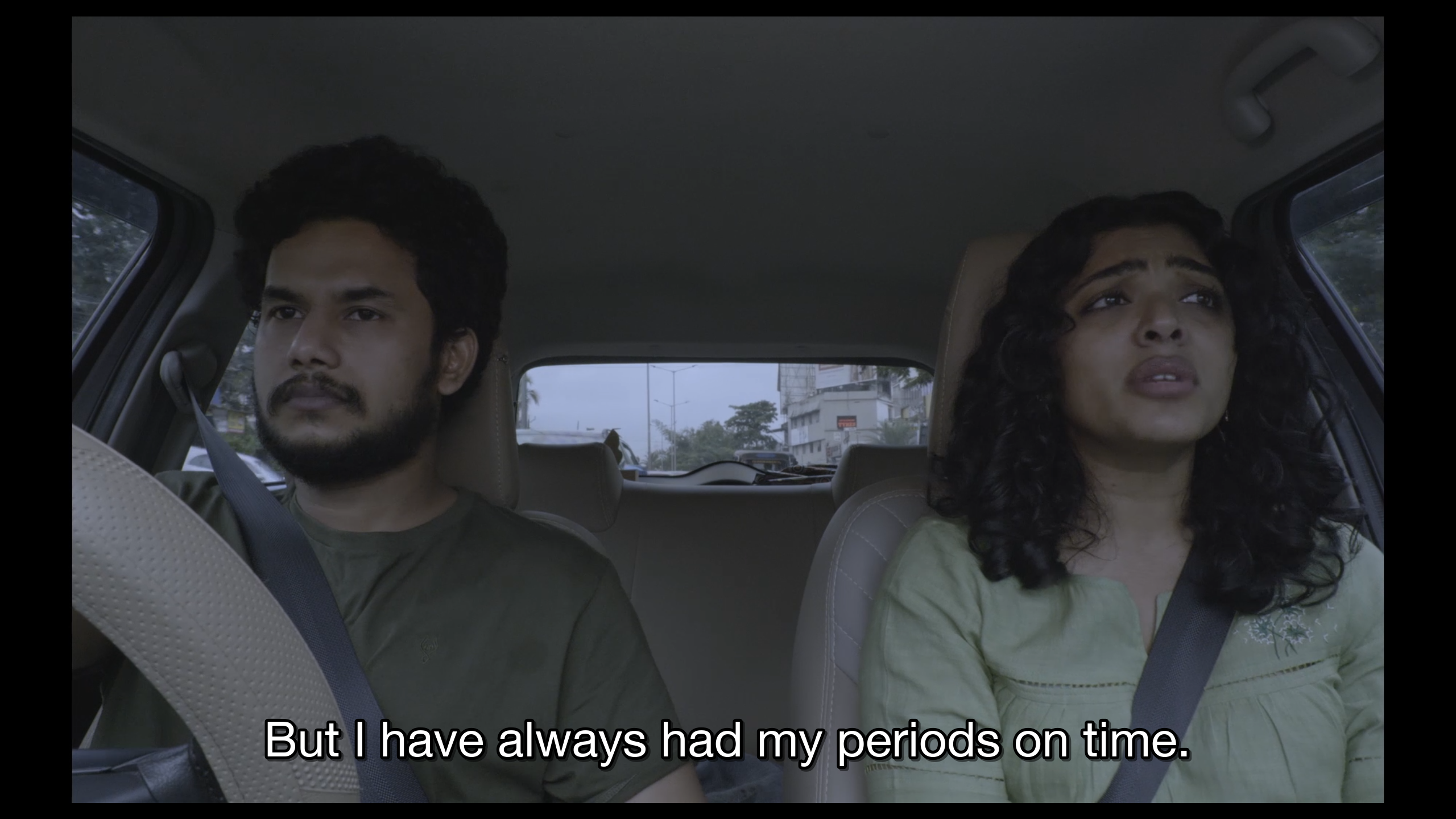

The above paragraphs reveal how the different themes on menstruation as manifested in Malayalam movies and their embedded meanings are coined from the male perspective of what menstruation is. That is, the asymmetry of gender power is a controlling force in the representations of menstruation in cinema and is ‘deeply rooted in patriarchal ideology and discourse’ (Mulvey, 1975). Accordingly, menstruation is often depicted as a bringer of disorder; as a marker of a woman’s sexual availability and reproductive capacity; as a comical aspect of the female body; or as something that doesn’t concern men. However, this doesn’t mean that the dominant narratives of menstruation are never challenged in Malayalam movies. Especially in recent times, attempts have been made at addressing the firm silence around the question of menstrual discrimination and to depict it as an affirmative element of the body and sexuality of women. For example, Ka Bodyscapes (Jayan Cherian, 2016) recreates an incident that happened in a private firm in Cochin in 2015 where ‘more than 40 women employees were strip searched by two female supervisors to identify the one who had left a used sanitary napkin in the bathroom’ (Prasanna, 2016, p. 94). Subsequently, one of the employees of the firm by the name Sia is shown as participating in an arthava samaram (menstrual uprising), where protestors shout slogans such as ‘my body, my right’ and ‘menstrual blood is not impure’. In one of the demonstrations, she is seen as walking with a bed sheet wrapped around her, with the image of a vagina drawn on it. She also uploads photographs of her soiled sanitary pads on Facebook. Similarly, the 2020 feature Santhoshathinte Onnam Rahasyamor SOR (Don Palathara, 2020) successfully depicts menstruation as it relates to women. The movie’s female protagonist Mariya addresses the intricacies of menstruation from the point of view of a woman – the Pre-Menstrual Symptoms, the anxieties surrounding a missed/delayed period, and the masculine ignorance regarding menstruation. In a series of heated arguments with her live-in partner, she even links menstruation and childbirth to a theory of gender and power by affirming that a woman’s biological processes certainly put her in a disadvantaged position in a patriarchal world. Thus, both Ka Bodyscapes and SOR,unlike the conventional patriarchal narratives of menstruation in Malayalam mainstream movies that vilify, romanticize and marginalize it, presents menstruation through the eyes and in the words of women. Yet, for ‘women’ is never a homogenous category, there is a huge diversity of menstrual experiences of different types of women – menopausal, rural, dysmenorrheic, and so on, whose experiences of menstruation are seldom represented on the silver screen. Perhaps, with the influx of menstrual activism and realistic filmmaking, such themes may soon get represented in the menstrual narratives of Malayalam cinema.

References

Bartky, S. L. (1995). Foucault, Femininity and the Modernization of Patriarchal Power. In K. Mehuron & G. Percesepe (Eds.) Free Spirits: Feminist Philosophers on Culture (pp. 240–256). NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Bemiller, M.L., & Schneider, R.Z. It’s Not Just a Joke. Sociological Spectrum, 30 (4), 459 – 479.

Bobel, C. (2010). New Blood: Third Wave Feminism and the Politics of Menstruation. New Brunswick, NJ & London: Rutgers University Press.

Douglas, M. (1966). Purity and Danger: An Analysis of Concepts of Pollution and Taboo. New York: Praeger.

Jose, N.K. (2018). The Shudra Revolt. Vaikom: Hobby Publications.

Kristeva, J. (1982). Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection. New York: Columbia University Press.

Laws, S. (1990). A sick Joke: Male Culture on Menstruation. In J. Campling (eds). Issues of Blood. London: Palgrave Macmillan

Lupton, D. (1998). The Emotional Self: A Sociocultural Exploration. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Mulvey, L. (1975). Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema. Oxford: Oxford Journal.

Newton, V.L. (2016). Everyday Discourses of Menstruation: Cultural and Social Perspectives. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Prasanna, C.K. (2016). Claiming the Public Sphere: Menstrual Taboos and the Rising Dissent in India. Agenda, 30 (3), 91- 95.

Schooler, D., Ward, M.L., Merriwether, A., & Caruthers, S.A. (2005). Cycles of Shame: Menstrual Shame, Body Shame, and Sexual Decision-Making. The Journal of Sex Research, 42 (4), 324-334.

Simon, B. (1987). Never Married Women. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Sherin Sabu is a doctoral scholar at the Department of Humanities and Social Sciences, IIT Bombay. She holds a B. A (honours) in Sociology from Lady Shri Ram College for Women, Delhi University and a post graduate degree in Social Work from Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai. Her PhD focuses on a socio cultural analysis of menstruation in central Kerala.